Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: September 25, 2023

Lead author: Judith Griffin, MD

Writing group: Susan D. Whitley, MD; Timothy J. Wiegand, MD; Sharon L. Stancliff, MD; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH

Committee: Substance Use Guidelines Committee

Date of original publication: August 29, 2019

This guideline on harm reduction was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to guide primary care clinicians and other clinical practitioners in integrating harm reduction principles into the treatment and care of adults with substance use and substance use disorders (SUDs).

Goals

By providing evidence-based guidelines on treatment of substance use and SUDs, the NYSDOH AI, and the Substance Use Guidelines Committee aim to increase the availability of treatment in general medical settings. With this guideline, the committee aims to promulgate a harm reduction approach to medical care of patients who use substances or have SUDs and to:

- Promote adoption of practical harm reduction strategies to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug and alcohol use.

- Increase awareness and use of NYSDOH and local/regional harm reduction resources.

- Support healthcare clinicians in recognizing and addressing the effects of stigma, which can pose a barrier to individuals seeking substance use treatment and harm reduction services.

Role of primary care clinicians: Primary care clinicians in New York State play an essential role in identifying substance use in patients, counseling patients about risky substance use, and expanding access to evidence-based treatment. SUDs are chronic conditions that can be successfully managed in primary care or other outpatient settings.

In the clinical context, harm reduction is an approach based on the use of practical strategies to reduce the negative consequences associated with substance use. It is founded on respect for and the rights of those individuals who use drugs (adapted from the National Harm Reduction Coalition). A harm reduction approach promotes positive changes beyond abstinence, which may include reducing substance use and using safely to reduce disease acquisition and transmission, and emphasizes the avoidance of coercion, discrimination, and bias in the clinical care of people with SUDs.

The NYSDOH AI and this committee strongly advocate a harm reduction approach in the care of all individuals who use substances, including those with a diagnosed SUD. The recommendations are based on emerging evidence and the extensive clinical experience of this committee.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic documented racial or ethnic disparities in access to evidence-based opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment Goedel, et al. 2020; Lagisetty, et al. 2019 and opioid overdose mortality rates Friedman, et al. 2022; Larochelle, et al. 2021. These disparities in access to treatment and mortality appear to have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic Kariisa, et al. 2022; Nguyen, et al. 2022; Khatri, et al. 2021.

Because people of color experience a disproportionate level of harm associated with substance use and repercussions related to use, it is essential to expand access to evidence-based harm reduction services and treatment for people of color who use substances. Clinicians can work directly with patients and their families and regular social contacts to provide naloxone and other harm reduction services when indicated and refer patients to appropriate community-based organizations for further support.

Harm Reduction During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had devastating consequences for people who use substances, with unprecedented increases in overdose deaths CDC 2023; Kouimtsidis, et al. 2021; Krawczyk, et al. 2021. In the United States, in the 12 months ending in April 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 75,673 opioid-related overdose deaths compared with 56,064 deaths in the preceding 12-month period CDC 2021. In 2019, 2,939 overdose deaths (14.9 per 100,000 population) occurred among New York State residents, which is nearly triple the rate in 2010 NYSDOH 2021. Preliminary 2020 data indicate the rate continues to increase; in New York State (excluding New York City), there were 2,521 (22.5 per 100,000 population) opioid-related deaths NYSDOH 2022.

Harm reduction interventions were implemented in response to COVID-19. For example, under the federal COVID Public Health Emergency (PHE), telemedicine was used to initiate medication for OUD treatment, thus expanding and protecting access to evidence-based treatment Jones, et al. 2022; Tofighi, et al. 2022; Wang, et al. 2021. The ability to initiate medication for OUD treatment via telehealth after the conclusion of the COVID PHE remains unclear at this time; PHE exemptions for telehealth have been extended through 2024 while new regulations are under review. Other harm reduction services implemented in response to the pandemic include home and mail-order delivery programs for naloxone distribution and syringe exchange.

Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma is more common among people with an SUD Bartholow and Huffman 2021; Karsberg, et al. 2021; Zarse, et al. 2019, and this population is more likely to experience trauma in healthcare settings Aronowitz and Meisel 2022; Simon, et al. 2020. The effect of trauma on the health and well-being of individuals and communities is gaining increasing visibility and attention CDC 2022; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 2022; Center for Youth Wellness 2017. Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced (or perceived) by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being SAMHSA 2014. Historical trauma refers to cumulative traumatic experience and associated harms extending over an individual life span and across generations. In a trauma-informed approach, clinicians recognize the signs of trauma and avoid retraumatizing patients.

| Resources |

|

Implementing Substance Use Harm Reduction

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Implementing Substance Use Harm Reduction

Overdose Prevention

Pharmacologic Treatment

|

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; NLX, naloxone; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SUD, substance use disorder. Notes:

|

Harm Reduction Approach

Substance use or SUDs, whether treated or not, do not preclude delivery of primary care services. Regardless of a patient’s desire to engage in treatment for substance use as part of their medical care, every clinic visit is an opportunity to provide primary care with attention to screening for sexually transmitted and injection drug use-associated diseases, including HIV and HCV, vaccinations, and sexual health services. See NYSDOH AI guidelines:

- HIV Testing

- Hepatitis C Virus Screening, Testing, and Diagnosis in Adults

- PrEP to Prevent HIV and Promote Sexual Health

- PEP to Prevent HIV Infection

Working with a patient who uses substances to implement an appropriate harm reduction/treatment plan involves balancing many factors, and choice may be limited by availability and other practical considerations. Some individuals may perceive substance use to be more helpful or pleasurable than harmful. Asking about and understanding the perceived benefits of substance use can help the clinician identify other ways for the patient to obtain the same or similar benefits and tailor a successful treatment plan.

Harm reduction/treatment goals: Traditionally, SUD treatment providers have considered abstinence the primary goal of treatment, but this approach is evolving. Changing the pattern of or reducing an individual’s substance use has measurable health benefits and contributes to increased function, even if the individual continues to use the substance of choice or other substances Charlet and Heinz 2017; Lea, et al. 2017; Collins(a), et al. 2015; Collins(b), et al. 2015; Gjersing and Bretteville-Jensen 2013.

For some individuals with a SUD, the use of other substances can reduce the use of the more problematic substance. There is increasing interest in the use of cannabis, cannabidiol, and other substances to reduce the compulsion to use opioids Chye, et al. 2019; Socías, et al. 2017. Choosing cannabis may be a harm reduction strategy for some patients who use opioids because fewer risks are associated with cannabis use.

One example of harm reduction counseling is to review with the patient any potential interactions between the substance(s) a patient uses and medications taken for other conditions and dispel misinformation about drug-drug interactions Kalichman(a), et al. 2022. In studies among individuals with HIV, intentional nonadherence to ART is associated with the belief that alcohol and other drugs interact with ART medications Kalichman(a), et al. 2022; Kalichman(b), et al. 2022; El-Krab and Kalichman 2021. If no significant interactions exist, patients should be encouraged to take all medications as prescribed even when using substances.

Based on individual patient needs and priorities and available clinical resources, clinicians should offer or refer patients for harm reduction services. Services may include primary or specialty medical care, education and counseling on safer drug use, development of an overdose safety plan including access to NLX, provision of sterile drug use equipment, provision of fentanyl and xylazine test strips or other options for drug checking, and referrals to social support resources.

Sterile syringes and needles and other drug equipment: Harm reduction includes the provision of or referral for sterile needles and syringes Bowman, et al. 2013. Sharing injection equipment can transmit bloodborne diseases, such as HIV and HCV; in the United States, injection drug use is the leading cause of HCV infection CDC 2018. Syringe access has been associated with dramatic reductions in HIV transmission; as syringe exchange was expanded in New York City, HIV seroincidence decreased to 1 per 100 person-years from 4 per 100 person-years Des Jarlais and Carrieri 2016. Syringe exchange has also been associated with reductions in HCV transmission Saab, et al. 2018; Des Jarlais, et al. 2005. Unsterile injection equipment is associated with soft tissue infections, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Candida albicans, and Staphylococcus aureus Hartnett, et al. 2019. It is also important for individuals who use drugs to have access to safe and sterile supplies beyond syringes, including alcohol swabs, ascorbic acid, sterile water, sterile cookers, sterile filters, tourniquets, straight stems, push sticks, brass screens, bowl pipes, mouthpieces, foil, paper straws, and benzalkonium wipes.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Opioid Overdose Prevention

Clinicians should provide patient education on the risks of overdose and discuss strategies to reduce overdose risk. See Box 1, below, for resources in New York State and the NYSDOH resource Your health and life matter. Build a safety plan.

Fentanyl: Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, is a common and often unidentified additive to heroin and other drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and counterfeit pills that look like various opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines Colon-Berezin, et al. 2019. Because fentanyl is much more potent than heroin, it increases the likelihood of a fatal opioid overdose. Clinicians should advise individuals who use drugs, both opioids and other drugs, on how to avoid an overdose: assume all products sold as heroin or other opioids will contain fentanyl and that stimulants and counterfeit pills may contain fentanyl, check drugs before use with a fentanyl test strip, avoid using alone, start with a small amount, carry NLX to reverse opioid overdoses, and avoid mixing drugs. If patients do use alone, counsel them to arrange for someone to check in with them; check-ins can be scheduled using phone- and web-based apps, such as Never Use Alone Inc.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Drug checking: Testing drugs with specialized equipment at a test site or with fentanyl test strips provides the chemical content of drugs before use. Some NYS Authorized Syringe Exchange Sites offer fentanyl test strips and drug checking with on-site gas chromatography-mass spectrometry machines that separate and detect chemical compounds.

Fentanyl test strips may promote safer use practices because individuals who are aware that drugs contain fentanyl may opt to use a smaller amount, change the mode of administration, or not use. Clinicians should discuss fentanyl test strips with patients who use opioids and other substances, such as methamphetamines, because of the presence of fentanyl in the nonprescription drug supply.

False-positive results erroneously showing the presence of fentanyl can occur when substances have been cut with high levels of diphenhydramine, methamphetamine, or 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) Lockwood, et al. 2021. Clinicians should counsel patients on how to use fentanyl test strips correctly, particularly when testing methamphetamines; if dilution is not performed correctly when testing methamphetamines, false-positive results may result. For more information on using fentanyl test strips, see NYC Health How to Test Your Drugs Using Fentanyl Test Strips.

Naloxone: Clinicians should prescribe or ensure access to NLX for individuals at risk of experiencing or witnessing an opioid overdose. As an opioid antagonist, NLX displaces other opioids from opioid receptors but does not cause opioid effects and does not have the potential for misuse. Clinicians should also encourage patients’ family members, friends, or other regular contacts to have NLX on hand and be trained to use it for reversing opioid overdose. The nasal spray formulation of NLX (“Narcan”) can be administered by laypeople and bystanders to reverse an opioid overdose safely and effectively. In New York State, intranasal NLX is covered by Medicaid, and the NYSDOH Naloxone Co-payment Assistance Program (see Box 1, below) covers a portion of the cost for patients with private insurance who have a copay for NLX. NLX is also distributed free of charge and regardless of insurance status by NYSDOH-Registered Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs.

The nasal spray formulation of NLX is typically prescribed and administered as a 4 mg dose. In 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an 8 mg dose of NLX nasal spray and a 5 mg prefilled syringe of NLX for intramuscular or subcutaneous injection to treat opioid overdose, but few clinical data are available that clarify when a higher dose or alternative administration method is indicated FDA 2021. A recent study of NLX 4 mg or 8 mg administration by New York State police first responders found that the same number of doses were administered regardless of formulation Payne, et al. 2024. In this study, there was no dose-related difference in survival, but the 8 mg dose was associated with more than twice the risk of withdrawal symptoms than the 4 mg dose. Ninety-nine percent of persons who received NLX, regardless of dose, survived.

The use of stimulants, either alone or in combination with other substances including opioids, has been increasing Han, et al. 2021, and no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatment is available specifically for stimulant use disorder. Individuals who use stimulants may be unknowingly exposed to fentanyl. As such, it is essential to offer NLX, fentanyl test strips, and other harm reduction strategies to patients who use nonprescription stimulants.

Overdose prevention centers (or sites): In December 2021, the first overdose prevention centers (OPCs) in the United States were opened in New York City. As of September 12, 2023, staff at the 2 New York City sites have reversed 1,008 overdoses, and a total of 3,719 individuals have used the sites; see OnPoint NYC.

OPCs, also known as “supervised injection facilities” or “supervised consumption sites” have been opened in 11 countries and are increasingly recognized as an evidence-based and cost-effective harm reduction intervention Samuels, et al. 2022. At an OPC, people can use drugs that they have obtained elsewhere under medical supervision. Sterile injection supplies are available, and staff are trained to monitor for overdose and administer oxygen, NLX, and other first-response care as needed. Additional medical and social services may be offered, including referrals to SUD treatment or other indicated services ICER 2021. Notably, an opinion study in the United States showed higher levels of support for “overdose prevention sites” than “supervised consumption sites” (45% vs. 29%), suggesting that using the term OPS (or OPC) may be preferred to foster public support Valencia, et al. 2021; Kennedy, et al. 2019; Barry, et al. 2018.

No fatal overdose has been reported in an OPC. Evidence demonstrates that OPCs are associated with improved outcomes, including reductions in overdose mortality ICER 2021; Levengood, et al. 2021; Kral, et al. 2020; Kennedy, et al. 2019, injection-related infections Valencia, et al. 2021, and injection risk behaviors, without increasing crime in the surrounding communities.

| Abbreviations: MATTERS, Medication for Addiction Treatment & Electronic Referrals; OASAS, Office of Addiction Services and Supports; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Notes:

|

|

| Box 1: Harm Reduction Resources in New York State (September 2023) | |

| Naloxone (NLX) |

|

| Sterile needles and syringes |

|

| Drug checking | Fentanyl test strips:

Xylazine test strips: |

| Drug user health hubs |

|

Pharmacologic Treatment for Substance Use Disorder

A range of effective pharmacologic treatments is available for several SUDs, including alcohol Jonas, et al. 2014; Rösner, et al. 2010; Overman, et al. 2003, tobacco Anthenelli, et al. 2016; Piper, et al. 2009, and opioid use disorders Lee, et al. 2018; Mattick, et al. 2014. Clinicians should discuss with patients the pharmacologic treatments and different treatment settings available and help them understand the benefits and risks. In New York State, most drug treatment programs licensed by the Office of Addiction Services and Supports are mandated to provide pharmacotherapy when indicated OASAS 2022. Some patients may misunderstand or have biases against pharmacologic treatment, so it may be helpful to continue these discussions over time.

Because the patient may benefit from treatment, clinicians should not deny or discontinue SUD treatment if a patient continues to or returns to use Gjersing and Bretteville-Jensen 2013. In 2017, the FDA issued a drug safety communication urging caution in denying methadone or buprenorphine when patients are taking benzodiazepines, because the risk of opioid overdose is higher with no treatment than the risks of combining the medications FDA 2017.

SUD is a chronic health condition that requires long-term management, including pharmacologic treatment Saitz, et al. 2013, which should be continued for as long as it is beneficial to the patient. Patients may opt to discontinue medication, but clinicians should encourage resumption without suggesting or implying that discontinuation of pharmacologic treatment is the preferred approach.

| KEY POINT |

|

Individualized follow-up during outpatient SUD treatment: Ongoing, regular follow-up is essential for support, encouragement, and modification of the treatment plan as needed.

- Follow-up within 2 weeks of treatment initiation allows tailoring of the treatment plan according to individual needs (e.g., change in dose of pharmacologic treatment, addition of support services).

- As patients stabilize on treatment, monthly or at least quarterly follow-up allows for ongoing evaluation to ensure that the patient’s goals are being met.

As with all diseases and disorders, patients who have a SUD may present with medical complexities beyond a clinician’s expertise. Adolescents may require specialty care, as may individuals who are pregnant or who have co-occurring psychiatric disorders. When individual patient factors complicate diagnosis and treatment, local and national resources are available for consultation and referral. For opioid-related issues, see Providers Clinical Support System or NYSDOH AI Provider Directory.

Avoiding Substance Use-Associated Discrimination

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Avoiding Substance Use-Associated Discrimination

|

Stigma in the Healthcare Setting

Substance use-related stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services Tsai, et al. 2019. In particular, people who use substances during pregnancy face significant stigma and may fear accessing medical care or other services as a result Schiff, et al. 2022; Wakeman, et al. 2021. Stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well documented Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013. Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015. In particular, the stigma associated with substance use may increase the risk of overdose, although the exact mechanism for this association is not well defined. In 1 study, enacted stigma (discrimination) was associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose but internalized stigma was not. This finding may suggest that enacted stigma could contribute to risk behaviors, such as using quickly or in multiple locations to avoid detection Latkin, et al. 2019; Cruz, et al. 2018.

It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012. Individuals who use substances may also be stigmatized by assumptions about substance use and criminal behavior. For more information, see the resources listed below.

| RESOURCES |

|

To acknowledge and address stigma, clinicians are advised to consciously change their substance use-related vocabulary to avoid stigmatizing terms, to use neutral medical terms, and to help colleagues and staff adopt neutral language (see Box 2, below). For example, the term “dirty urine test” elicits a more negative reaction toward a patient than the more accurate and neutral term “opiate-positive test result” Kelly and Westerhoff 2010. Patients may choose to use stigmatizing words in describing themselves, but clinicians and staff should strive to use language that is respectful of the individual and easy to understand.

Notes:

|

|

| Box 2: Changing the Language of Substance Use [a,b] | |

| Neutral Term | Stigmatizing Term |

| Substance use | Substance abuse |

| Use of nonprescription medication or drug | Illicit drug use |

| Pharmacologic treatment | Medication-assisted treatment |

| A person who uses drugs, alcohol, or substances | Drug addict, drug abuser, alcoholic, junkie, crackhead, tweaker, etc. |

| A person who formerly used drugs or alcohol | A person who got clean |

| Negative or positive toxicology results | Clean or dirty toxicology results |

| A recurrence of use or return to use | Relapse |

Legal Protections for Individuals With Substance Use Disorder

The New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL) and the American With Disabilities Act (ADA) protect individuals with disabilities from discrimination in the workplace and housing. Under the NYSHRL and ADA, individuals taking prescribed medical treatment for SUD and those in recovery from SUD are considered disabled; for patients with OUD, see The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Opioid Crisis: Combating Discrimination Against People in Treatment or Recovery. The NYSHRL and the ADA exclude from protection individuals who are currently using illegal drugs.

Employers and housing providers are prohibited from discriminating against individuals with disabilities under the NYSHRL. Employers are prohibited from denying a job opportunity to a qualified individual, terminating an employee because of a disability, and making inquiries about an individual’s disability, which includes questions about prescribed medical care for SUD. Employers are to provide reasonable accommodations to assist disabled people in performing their job functions. It is unlawful for housing providers to refuse to house or discriminate against a tenant because they are taking medical treatment for SUD or are in recovery from SUD.

Information about these protections and enforcement of the NYSHRL can be found at the New York State Division of Human Rights.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: SUBSTANCE USE HARM REDUCTION IN MEDICAL CARE |

Implementing Substance Use Harm Reduction

Overdose Prevention

Pharmacologic Treatment

Avoiding Substance Use-Associated Discrimination

|

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; NLX, naloxone; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SUD, substance use disorder. Notes:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

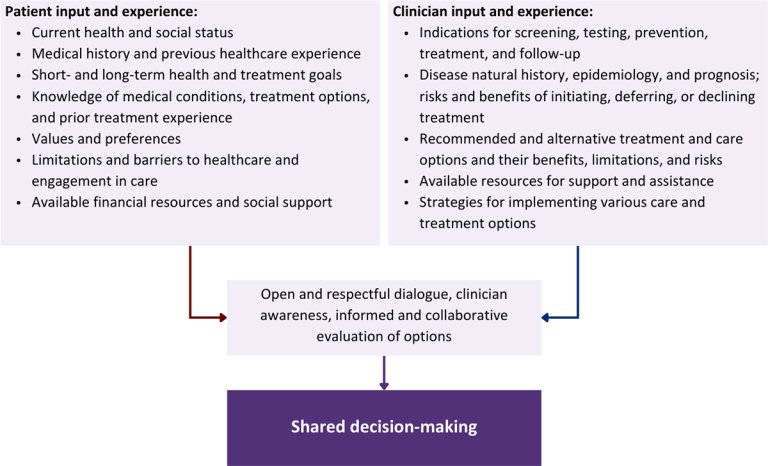

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Anthenelli R. M., Benowitz N. L., West R., et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2016;387(10037):2507-20. [PMID: 27116918]

Aronowitz S., Meisel Z. F. Addressing stigma to provide quality care to people who use drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(2):e2146980. [PMID: 35119465]

Avery J. D., Taylor K. E., Kast K. A., et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Barry C. L., Sherman S. G., McGinty E. E. Language matters in combatting the opioid epidemic: safe consumption sites versus overdose prevention sites. Am J Public Health 2018;108(9):1157-59. [PMID: 30088990]

Bartholow L. A., Huffman R. T. The necessity of a trauma-informed paradigm in substance use disorder services. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2021;10783903211036496. [PMID: 34334012]

Bowman S., Eiserman J., Beletsky L., et al. Reducing the health consequences of opioid addiction in primary care. Am J Med 2013;126(7):565-71. [PMID: 23664112]

CDC. Surveillance for viral hepatitis – United States, 2016. 2018 Apr 16. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2016surveillance/index.htm [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. top 100,000 annually. 2021 Nov 17. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

CDC. VetoViolence. 2022 Mar 22. https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/apps/aces-infographic/home [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

CDC. National Vital Statistics System: provisional drug overdose death counts. 2023 Feb 15. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

Center for Youth Wellness. The landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. 2017. https://centerforyouthwellness.org/the-science/ [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

Charlet K., Heinz A. Harm reduction-a systematic review on effects of alcohol reduction on physical and mental symptoms. Addict Biol 2017;22(5):1119-59. [PMID: 27353220]

Chye Y., Christensen E., Solowij N., et al. The endocannabinoid system and cannabidiol's promise for the treatment of substance use disorder. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:63. [PMID: 30837904]

Collins(a) S. E., Duncan M. H., Smart B. F., et al. Extended-release naltrexone and harm reduction counseling for chronically homeless people with alcohol dependence. Subst Abus 2015;36(1):21-33. [PMID: 24779575]

Collins(b) S. E., Grazioli V. S., Torres N. I., et al. Qualitatively and quantitatively evaluating harm-reduction goal setting among chronically homeless individuals with alcohol dependence. Addict Behav 2015;45:184-90. [PMID: 25697724]

Colon-Berezin C., Nolan M. L., Blachman-Forshay J., et al. Overdose deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs - New York City, 2000-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(2):37-40. [PMID: 30653482]

Cruz C. C., Salom C., Maravilla J., et al. Mental and physical health correlates of discrimination against people who inject drugs: a systematic review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2018;79(3):350-60. [PMID: 29885142]

Des Jarlais D. C., Carrieri P. HIV infection among persons who inject drugs: ending old epidemics and addressing new outbreaks: authors' reply. AIDS 2016;30(11):1858-59. [PMID: 27351930]

Des Jarlais D. C., Perlis T., Arasteh K., et al. Reductions in hepatitis C virus and HIV infections among injecting drug users in New York City, 1990-2001. AIDS 2005;19 Suppl 3:s20-25. [PMID: 16251819]

El-Krab R., Kalichman S. C. Alcohol-antiretroviral therapy interactive toxicity beliefs and intentional medication nonadherence: review of research with implications for interventions. AIDS Behav 2021;25(Suppl 3):251-64. [PMID: 33950339]

FDA. FDA drug safety communication: FDA urges caution about withholding opioid addiction medications from patients taking benzodiazepines or CNS depressants: careful medication management can reduce risks. 2017 Sep 26. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-urges-caution-about-withholding-opioid-addiction-medications [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

FDA. FDA approves higher dosage of naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose. 2021 May 11. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-higher-dosage-naloxone-nasal-spray-treat-opioid-overdose [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

FitzGerald C., Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Friedman J., Beletsky L., Jordan A. Surging racial disparities in the U.S. overdose crisis. Am J Psychiatry 2022;179(2):166-69. [PMID: 35105165]

Gjersing L., Bretteville-Jensen A. L. Is opioid substitution treatment beneficial if injecting behaviour continues?. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;133(1):121-26. [PMID: 23773951]

Goedel W. C., Shapiro A., Cerdá M., et al. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(4):e203711. [PMID: 32320038]

Hall W. J., Chapman M. V., Lee K. M., et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Han B., Compton W. M., Jones C. M., et al. Methamphetamine use, methamphetamine use disorder, and associated overdose deaths among US adults. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78(12):1329-42. [PMID: 34550301]

Hartnett K. P., Jackson K. A., Felsen C., et al. Bacterial and fungal infections in persons who inject drugs - Western New York, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(26):583-86. [PMID: 31269011]

ICER. Supervised injection facilities and other supervised consumption sites: effectiveness and value. 2021 Jan 8. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_SIF_Final-Evidence-Report_010821.pdf [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

Jonas D. E., Amick H. R., Feltner C., et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311(18):1889-1900. [PMID: 24825644]

Jones C. M., Shoff C., Hodges K., et al. Receipt of telehealth services, receipt and retention of medications for opioid use disorder, and medically treated overdose among medicare beneficiaries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2022;79(10):981-92. [PMID: 36044198]

Kalichman(a) S. C., Eaton L. A., Kalichman M. O. Believing that it is hazardous to mix alcohol with medicines predicts intentional nonadherence to antiretrovirals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2022;90(2):208-13. [PMID: 35125476]

Kalichman(b) S. C., Eaton L. A., Kalichman M. O. Perceived sensitivity to medicines and medication concerns beliefs predict intentional nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among young people living with HIV. Psychol Health 2022;1-16. [PMID: 36111623]

Kariisa M., Davis N. L., Kumar S., et al. Vital signs: drug overdose deaths, by selected sociodemographic and social determinants of health characteristics - 25 states and the District of Columbia, 2019-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71(29):940-47. [PMID: 35862289]

Karsberg S., Hesse M., Pedersen M. M., et al. The impact of poly-traumatization on treatment outcomes in young people with substance use disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21(1):140. [PMID: 33685430]

Kelly J. F., Westerhoff C. M. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy 2010;21(3):202-7. [PMID: 20005692]

Kennedy M. C., Hayashi K., Milloy M. J., et al. Supervised injection facility use and all-cause mortality among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada: a cohort study. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002964. [PMID: 31770391]

Khatri U. G., Pizzicato L. N., Viner K., et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in unintentional fatal and nonfatal emergency medical services-attended opioid overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Philadelphia. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(1):e2034878. [PMID: 33475751]

Kouimtsidis C., Pauly B., Parkes T., et al. COVID-19 social restrictions: an opportunity to re-visit the concept of harm reduction in the treatment of alcohol dependence. A position paper. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:623649. [PMID: 33679480]

Kral A. H., Lambdin B. H., Wenger L. D., et al. Evaluation of an unsanctioned safe consumption site in the United States. N Engl J Med 2020;383(6):589-90. [PMID: 32640126]

Krawczyk N., Fawole A., Yang J., et al. Early innovations in opioid use disorder treatment and harm reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2021;16(1):68. [PMID: 34774106]

Lagisetty P. A., Ross R., Bohnert A., et al. Buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76(9):979-81. [PMID: 31066881]

Larochelle M. R., Slavova S., Root E. D., et al. Disparities in opioid overdose death trends by race/ethnicity, 2018-2019, from the HEALing Communities Study. Am J Public Health 2021;111(10):1851-54. [PMID: 34499540]

Latkin C. A., Gicquelais R. E., Clyde C., et al. Stigma and drug use settings as correlates of self-reported, non-fatal overdose among people who use drugs in Baltimore, Maryland. Int J Drug Policy 2019;68:86-92. [PMID: 31026734]

Lea T., Kolstee J., Lambert S., et al. Methamphetamine treatment outcomes among gay men attending a LGBTI-specific treatment service in Sydney, Australia. PLoS One 2017;12(2):e0172560. [PMID: 28207902]

Lee J. D., Nunes E. V., Novo P., et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391(10118):309-18. [PMID: 29150198]

Levengood T. W., Yoon G. H., Davoust M. J., et al. Supervised injection facilities as harm reduction: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2021;61(5):738-49. [PMID: 34218964]

Livingston J. D., Milne T., Fang M. L., et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

Lockwood T. E., Vervoordt A., Lieberman M. High concentrations of illicit stimulants and cutting agents cause false positives on fentanyl test strips. Harm Reduct J 2021;18(1):30. [PMID: 33750405]

Mattick R. P., Breen C., Kimber J., et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(2):CD002207. [PMID: 24500948]

Nguyen T., Ziedan E., Simon K., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone filled prescriptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(6):e2214765. [PMID: 35648400]

NYSDOH. New York State opioid annual data report 2020. 2021 Jul 16. https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/opioid/data/pdf/nys_opioid_annual_report_2020.pdf [accessed 2022 Sep 8]

NYSDOH. New York State - county opioid quarterly report. 2022 Jul. https://health.ny.gov/statistics/opioid/data/pdf/nys_jul22.pdf [accessed 2022 Sep 8]

OASAS. OASAS services: general provisions. Title 14 NYCRR part 800. 2022 Oct 1. https://oasas.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2022/09/800.pdf [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

Overman G. P., Teter C. J., Guthrie S. K. Acamprosate for the adjunctive treatment of alcohol dependence. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37(7-8):1090-99. [PMID: 12841823]

Payne E. R., Stancliff S., Rowe K., et al. Comparison of administration of 8-milligram and 4-milligram intranasal naloxone by law enforcement during response to suspected opioid overdose - New York, March 2022-August 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73(5):110-13. [PMID: 38329911]

Piper M. E., Smith S. S., Schlam T. R., et al. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66(11):1253-62. [PMID: 19884613]

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Adverse childhood experiences. 2022. https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/collections/adverse-childhood-experiences.html [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

Rösner S., Hackl-Herrwerth A., Leucht S., et al. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(12):CD001867. [PMID: 21154349]

Saab S., Le L., Saggi S., et al. Toward the elimination of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 2018;67(6):2449-59. [PMID: 29181853]

Saitz R., Cheng D. M., Winter M., et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310(11):1156-67. [PMID: 24045740]

SAMHSA. Concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. 2014 Jul. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf [accessed 2022 Sep 29]

Samuels E. A., Bailer D. A., Yolken A. Overdose prevention centers: an essential strategy to address the overdose crisis. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(7):e2222153. [PMID: 35838675]

Schiff D. M., Stoltman J. J., Nielsen T. C., et al. Assessing stigma towards substance use in pregnancy: a randomized study testing the impact of stigmatizing language and type of opioid use on attitudes toward mothers with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med 2022;16(1):77-83. [PMID: 33758119]

Simon R., Snow R., Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: a qualitative study. Subst Abus 2020;41(4):519-25. [PMID: 31638862]

Socías M. E., Kerr T., Wood E., et al. Intentional cannabis use to reduce crack cocaine use in a Canadian setting: a longitudinal analysis. Addict Behav 2017;72:138-43. [PMID: 28399488]

Stone E. M., Kennedy-Hendricks A., Barry C. L., et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians' treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tofighi B., McNeely J., Walzer D., et al. A telemedicine buprenorphine clinic to serve New York City: initial evaluation of the NYC public hospital system's initiative to expand treatment access during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Addict Med 2022;16(1):e40-43. [PMID: 33560696]

Tsai A. C., Kiang M. V., Barnett M. L., et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Valencia J., Troya J., Lazarus J. V., et al. Recurring severe injection-related infections in people who inject drugs and the need for safe injection sites in Madrid, Spain. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021;8(7):ofab251. [PMID: 34250189]

van Boekel L. C., Brouwers E. P., van Weeghel J., et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

Wakeman B., Kremer M., Schulkin J. The application of harm reduction to methamphetamine use during pregnancy: a call to arms. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3(5):100418. [PMID: 34102337]

Wang L., Weiss J., Ryan E. B., et al. Telemedicine increases access to buprenorphine initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Subst Abuse Treat 2021;124:108272. [PMID: 33771276]

Zarse E. M., Neff M. R., Yoder R., et al. The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Medicine 2019;6(1):1581447. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2019.1581447

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | August 29, 2019 |

| Date of current publication | September 25, 2023 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the September 25, 2023 edition |

Updated text on opioid overdose prevention counseling and resources for obtaining fentanyl and xylazine test strips in New York State |

| Intended users | Primary care clinicians and other practitioners in New York State with adult patients who use substances |

| Lead author |

Judith Griffin, MD |

| Writing group |

Susan D. Whitley, MD; Timothy J. Wiegand, MD; Sharon L. Stancliff, MD; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI guidelines | |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on April 18, 2024