Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: January 24, 2022

Lead authors: Deepika Slawek, MD, MS, MPH; Julia H. Arnsten, MD, MPH

Writing group: Susan D. Whitley, MD; Timothy J. Wiegand, MD, FACMT, FAACT, DFASAM; Sharon Stancliff, MD; Lyn C. Stevens, MS, NP, ACRN; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Substance Use Guidelines Committee

Date of original publication: January 24, 2022

This guideline on the therapeutic use of medical cannabis in New York State was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to accomplish the following:

- Provide clinicians with a framework for implementing the therapeutic use of medical cannabis in their outpatient settings in New York State.

- Increase access to evidence-based medical cannabis treatment for ambulatory patients in New York State by increasing the number of clinicians who can provide that care in outpatient settings (see Increasing Access to Safe Medical Cannabis).

Use of Medical Cannabis in New York State

In 2014, New York State passed the Compassionate Care Act to create a program to safely and effectively provide medical cannabis to eligible state residents. In 2016, the New York State Medical Cannabis Program (NYSMCP) was implemented (see Box 1, below). Through the NYSMCP, the NYSDOH identifies the medical conditions that qualify patients for medical cannabis treatment in New York State (see Box 2: Current Indications for Medical Cannabis Certification in New York State). Trained, registered care providers evaluate patients to determine eligibility for medical cannabis treatment. If eligible, patients are certified and register online to receive a registry identification card that allows them to purchase medical cannabis from a registered dispensary. As of February 2022, more than 124,000 patients have been certified, and more than 3,500 clinicians have registered as medical cannabis providers in New York State. The Public List of Consenting Medical Cannabis Program Practitioners provides registered care providers’ names, locations, and contact information.

Registered dispensing facilities in New York State sell medical cannabis products that have been tested by independent third-party laboratories, to ensure the specified delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) content and to detect potential contaminants, and are approved for sale by the Office of Cannabis Management (see Table 2: Medical Cannabis Administration Methods Currently Available in New York State). Available products include oils for vaporization, tinctures, capsules, chewable gels, and whole and ground cannabis flower packaged for use in a vaporizer device. Edible cannabis and cannabis for smoking by combustion are not available by prescription or distributed in registered dispensing facilities. The Marihuana Regulation and Taxation Act (MRTA) introduced home cultivation of medical cannabis for certified patients and caregivers.

In March 2021, legislation legalizing adult cannabis use in New York State was signed, creating the Office of Cannabis Management to implement a comprehensive regulatory framework for medical cannabis use, adult cannabis use, and cannabinoid hemp product use.

Under federal law, per the U.S. Controlled Substance Act, Food and Drug Administration, and U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, cannabis is “a Schedule I controlled substance with no federally approved medical use for treatment in the U.S.”DEA 2020. The federal legal status of cannabis has severely limited the ability to conduct high-quality, rigorous research on the medical use of cannabis and limits the availability of published evidence FDA 2020. Enforcement of federal cannabis laws is fluid and depends upon Department of Justice enforcement, which changes according to the administration in the Executive Branch NCSL 2021.

The NYSMCP provides protections to practitioners who abide by program regulations. However, care providers who do not follow NYSMCP program regulations or the MRTA could face legal consequences New York State Assembly 2014.

Because of the lack of rigorous evidence for the therapeutic use of medical cannabis, some medical organizations recommend against its use, including the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Medical Association. However, other professional societies, including the American Society of Addiction Medicine and the American Academy of Family Physicians, have more nuanced policies and recommend that medical cannabis be used only in circumstances in which a true patient—healthcare provider relationship is established with appropriate follow-up and that a health department regulate medical cannabis programs. Ultimately, patients are using and want to use medical cannabis National Academies of Sciences 2017. It is important to understand how to discuss it with them and to encourage safe use of medical cannabis as a harm reduction principle or when other treatment modalities have failed.

| Box 1: New York State Medical Cannabis Program |

The New York State Medical Cannabis Program website offers extensive information and resources to clinicians, including:

|

Medical Cannabis Providers

When indicated, clinicians can refer patients to New York State-registered cannabis providers for assessment and certification. New York State clinicians who wish to become registered medical cannabis providers must complete required training through the NYSMCP; once registered, they can assess patients and recommend cannabis products, delivery methods, initial dosing, and dosing adjustments. Clinicians can either restrict patient certification to certain products or elect to have a pharmacist at the dispensary determine which products a patient can purchase. In New York State, dispensing facilities are required to have a licensed pharmacist on the premises to supervise activity whenever medical cannabis products are dispensed or handled. These pharmacists have experience with dosing based on individual clinical symptoms and have completed an online curriculum approved by the State.

Definition of Terms

Table 1, below, explains terms used throughout this guideline.

| Abbreviation: FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. | |

| Table 1: Terms Used in This Guideline | |

| Term | Definition |

| Cannabis and Cannabinoid Products | |

| Cannabis | A broad term describing various products and chemical compounds derived from the Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica species National Academies of Sciences 2017. |

| Marijuana | Leaves, stems, seeds, and flower buds derived from the Cannabis plant National Academies of Sciences 2017. |

| Hemp | Cannabis plant with very low levels of THC (<0.3%) Small 2015. |

| Unregulated cannabis | Cannabis that is not obtained from a licensed cannabis dispensing facility, does not undergo testing for contaminants or to confirm cannabinoid content by New York State, and is not recommended by a medical care provider. |

| Regulated adult-use cannabis | Legal cannabis that has undergone testing for contaminants and to confirm cannabinoid content by New York State. Does not require evaluation by a medical care provider to dispense to an individual. |

| Medical cannabis | Legal cannabis that has undergone testing for contaminants and to confirm cannabinoid content by New York State. Dispensed under the purview of recommendations from a medical care provider. |

| Dronabinol/nabilone | Orally administered medications with synthetic THC as the active ingredient. Approved by the FDA to treat anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with HIV (dronabinol) and nausea/vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy in patients who have not responded adequately to conventional antiemetic treatments (dronabinol or nabilone) FDA 2017; FDA 2006. |

| Constituents | |

| Cannabinoid | One of a group of over 100 biologically active chemicals found in the cannabis plant. |

| delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | The main psychoactive constituent of cannabis National Academies of Sciences 2017. |

| Cannabidiol (CBD) | A constituent of cannabis traditionally considered nonpsychoactive National Academies of Sciences 2017. A purified form of CBD is approved by the FDA for treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome, or tuberous sclerosis complex in patients 1 year of age and older FDA(b) 2018. |

| THC:CBD ratio | The ratio of THC to CBD in a medical cannabis product. |

| Terpenes | Compounds that produce the plant’s smell, taste, and appearance (e.g., limonene, myrcene). |

| Medical Cannabis Terminology | |

| Administration method | In New York State, the currently available administration methods for medical cannabis are inhaled, oral, sublingual, topical, and suppository. Inhaled products currently include vaporized oil and vaporized whole or ground flower. |

| Care provider registration | An educational process by which a medical care provider becomes eligible to certify patients for medical cannabis use. |

| Medical cannabis certification | A patient assessment completed by a practitioner registered in the New York State Medical Cannabis Program to certify that the patient has a qualifying severe debilitating condition(s) necessary for medical cannabis eligibility in New York State. |

| Medical cannabis registration | Patients complete the online process to become registered to receive medical cannabis. Once completed, patients receive a New York State registration identification card. |

| Dispensing facility | A retail site of an organization registered with New York State to dispense medical cannabis under the supervision of a pharmacist to individuals with medical cannabis certification. |

| Quantification of and Approach to Cannabis Use | |

| Less frequent or no cannabis use | Cannabis use on less than 20 days in a month Compton, et al. 2016. |

| Near-daily or heavy cannabis use | Cannabis use on at least 20 days of the month Compton, et al. 2016. |

| Harm reduction | In the clinical context, an approach and practical strategies targeted to reduce the negative consequences of substance use. It is founded on respect for the rights of individuals who use drugs [adapted from the National Harm Reduction Coalition]. |

Cannabis Pharmacology and the Endocannabinoid System

“Cannabis” describes a family of plants including Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, and hemp. The cannabis plant produces more than 100 cannabinoids and a similar number of terpenes. The most widely studied cannabinoids are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). The other cannabinoids may contribute to the therapeutic effect of cannabis Huestis 2007, and terpenes (e.g., limonene, myrcene) produce the smell, taste, and appearance of the plant. Cannabinoids can be endogenous (endocannabinoid), plant-derived (phytocannabanoid), or synthetic and act as neurotransmitters within the human endocannabinoid system. Cannabinoid receptors in the endocannabinoid system are called CB1 and CB2 Munro, et al. 1993; Matsuda, et al. 1990.

CB1 receptors exist primarily in areas of the brain that regulate appetite, memory, fear, and motor responses. Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the brain produces psychotropic effects. CB1 receptors are also found outside the brain in the gastrointestinal tract, adipocytes, liver, and skeletal muscle Mackie 2005; Matsuda, et al. 1990. CB2 is primarily expressed in macrophages and other macrophage-derived cells that are part of the immune system Munro, et al. 1993.

Current understanding of cannabis pharmacology is incomplete, and much remains under investigation. Both THC and CBD act on CB1 and CB2 receptors but in different ways. THC is a partial agonist of CB1 and CB2 receptors. Stimulation of these receptors by THC leads to analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and muscle-relaxant effects Pertwee 2006. The binding of THC to CB1 receptors is associated with psychoactive features, including reduced or enhanced anxiety, memory suppression, euphoria, and intoxication. Stimulation of CB2 receptors leads to anti-inflammatory effects Russo and Guy 2006. CBD binds weakly to CB1 and CB2 receptors Russo and Guy 2006, producing anti-inflammatory Ben-Shabat, et al. 2006, antispasmodic Wade, et al. 2006, and analgesic effects Maione, et al. 2011. When THC and CBD are used together, several other receptors are activated to regulate pain perception Russo and Guy 2006.

Therapeutic Uses of Cannabis

Evidence supporting the most common current uses of medical cannabis is summarized below. To be certified for medical cannabis use in New York State, patients must have a qualifying condition, which are detailed in Box 2, below, and based on New York State legislation. The Marihuana Regulation and Taxation Act (MRTA), signed into law March 31, 2021, expands the medical program to include Alzheimer disease, muscular dystrophy, dystonia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autism as qualifying conditions. The MRTA also affords providers the authority to use their clinical discretion to certify their patients for any other condition for which the patient is likely to receive therapeutic or palliative benefit from the primary or adjunctive treatment with medical cannabis. Consult the New York State Medical Cannabis Program website to find the most up-to-date list of qualifying conditions.

| Box 2: Current Indications for Medical Cannabis Certification in New York State (as of January 2022) See New York State Medical Cannabis Program for the most up-to-date information. |

|

Qualifying Condition (Must be specified in the patient health care record.)

|

|

Previously, the program had a list of associated conditions that were required for patient certification in addition to the qualifying conditions (including opioid use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, seizures, severe nausea, severe or persistent muscle spasms, severe or chronic pain resulting in substantial limitation of function, and cachexia or wasting syndrome). Associated conditions are no longer required under the MRTA.

Chronic or severe pain: The most common condition for which patients are certified to receive medical cannabis in New York State is chronic or severe pain NYSDOH 2018 that degrades health and functional capability and might otherwise be treated with opioids. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that, compared with placebo, the use of cannabinoids is more likely to result in ≥30% reduction in pain scores Whiting, et al. 2015. Of the 28 RCTs reviewed, 22 evaluated plant-derived cannabinoids and most used a placebo control. Most studies used a plant-derived medical cannabis product developed for medical use outside of the United States. The remainder evaluated cannabis in flower form, which can be obtained for research studies from the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Academies of Sciences 2017.

Severe or persistent muscle spasms: Cannabinoid use for the management of spasticity has been studied primarily in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). One systematic review identified 27 studies (8 RCTs) examining spasticity in adults Nielsen, et al. 2019; 21 of these studies included adults with MS. Spasticity improved in participants in the 8 RCTs, although spasticity improvement was based on participant- rather than clinician-rated measures, and the few RCTs that used clinician-rated measures for spasticity used the now outdated Modified Ashworth Scale Nielsen, et al. 2019; Ansari, et al. 2006. In another meta-analysis, investigators conducted a pooled analysis of data from 3 studies that used numerical rating scales in investigating the efficacy of cannabinoids for spasticity in MS Whiting, et al. 2015. Compared with placebo, formulations of cannabis with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) were associated with improved spasticity on a participant-reported rating scale, and greater improvements in symptoms were reported by participants who received coformulated THC and CBD (compared with those who received THC alone).

As with the research on chronic pain, these studies were all conducted with forms of medical cannabis that are not the same as those provided to medical cannabis patients in New York State. However, the cannabis studied contained the same primary active ingredients (THC and CBD) as the medical cannabis currently available in New York State.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): PTSD was added as a qualifying condition for the New York State Medical Cannabis Program (NYSMCP) in November 2017. The efficacy of cannabis for managing PTSD is not well studied Lowe, et al. 2019. Several small studies have examined THC for the treatment of nightmares, insomnia, and other PTSD symptoms, mostly in combat veterans Jetly, et al. 2015; Cameron, et al. 2014; Roitman, et al. 2014; Fraser 2009. In all of these studies, participants experienced improved sleep, as measured by a reduction in the number or intensity of nightmares or improvements in overall sleep quality. Concern remains that cannabis use in people with PTSD may result in adverse outcomes; however, this is also not well studied Lowe, et al. 2019.

Severe nausea: Few studies have examined medical cannabis use to treat severe nausea National Academies of Sciences 2017. Oral synthetic THC (nabilone or dronabinol) has been used to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea for decades. It is superior to placebo and equally efficacious to comparator antiemetics Grotenhermen and Müller-Vahl 2012. CBD is less well studied in humans for the management of nausea than THC. In animal studies, CBD alone was an effective anti-nausea agent Whiting, et al. 2015; Rock, et al. 2012.

Cachexia or wasting: There is very limited evidence that cannabis is effective in the management of cachexia or wasting. The use of cannabis for cachexia or wasting has been studied primarily in either AIDS wasting syndrome or cancer-associated cachexia. In an article summarizing 4 RCTs that investigated the effect of cannabis in individuals with AIDS wasting syndrome, the author concluded that these trials had a high risk of bias, but there is some evidence that cannabis is effective for weight gain in individuals with HIV Whiting, et al. 2015. All 4 of these studies compared dronabinol (synthetic THC) with placebo or megestrol acetate. For cancer-associated cachexia, a phase 3 multicenter RCT compared treatment with cannabis extract (THC and CBD), THC alone, and placebo for 6 weeks. Participants (164 total) were monitored for appetite, mood, and nausea, with no significant differences between the 3 groups. Recruitment was terminated early because the data review board determined differences between groups were unlikely to emerge Strasser, et al. 2006. In a more recent pilot study, 17 individuals with cancer-associated cachexia were enrolled and received high THC:low CBD cannabis capsules for 6 months. Only 6 participants completed the study, 3 of whom had a weight gain of ≥10% from baseline; weight remained stable in the other participants Bar-Sela, et al. 2019.

Seizures: In June 2018, CBD was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat rare forms of childhood epilepsy: Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex FDA(a) 2018. Dravet syndrome is a complex childhood epilepsy disorder associated with treatment-resistant seizures and a high mortality rate. In a double-blind RCT, daily oral CBD was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the frequency of convulsive seizures Devinsky, et al. 2017. In Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, another childhood epilepsy disorder with treatment-resistant seizures, CBD use resulted in a 41% reduction in seizure frequency. Reduction in seizure frequency was dose-dependent Devinsky, et al. 2018.

The use of cannabinoids to manage seizures in adults and children with more common forms of epilepsy is not as well studied. In an open-label study of CBD use in 70 pediatric and 62 adult participants with treatment-resistant epilepsy, 64% of participants experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Participants also experienced reduced severity of seizures and fewer adverse events Szaflarski, et al. 2018. In a small study of 21 adult participants with treatment-resistant seizures, CBD use was associated with a 71% reduction in seizure frequency, an 80% reduction in seizure severity, and improved mood Allendorfer, et al. 2019. These outcomes are very encouraging but were achieved with doses of CBD alone that exceed the doses approved for sale by the NYSMCP. Beyond CBD, there is little evidence to support taking other cannabinoids to manage seizures Perucca 2017.

Opioid use: Medical cannabis treatment has emerged as a strategy to address the opioid epidemic. Amendments to the New York State Medical Use of Marijuana regulations in 2018 added substance use disorder as a serious condition that qualifies for medical cannabis use (see Box 2, above) NYSDOH 2018.

In several ecological studies, medical cannabis use has been associated with reduced opioid-related deaths, opioid prescribing, and opioid use Bradford, et al. 2018; Powell, et al. 2018; Bradford and Bradford 2017; Boehnke, et al. 2016; Bachhuber, et al. 2014. However, more recent studies found that opioid overdose mortality increased in U.S. states where medical cannabis is available Shover, et al. 2019; Caputi and Humphreys 2018. Because these studies were retrospective and observational, it is impossible to eliminate confounding factors and determine causality. The observed benefits of cannabis on opioid-related pain outcomes are due to its analgesic effect, but evidence to support taking medical cannabis to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) is scant. Randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to understand the relationship between medical cannabis use and opioid-related outcomes.

There are well-established OUD treatments based on a strong evidence base. Buprenorphine and methadone are the standard of care for OUD and are effective in retaining patients in treatment and reducing illicit opioid use Mancher and Leshner 2019; Hser, et al. 2016; Timko, et al. 2016; Mattick, et al. 2014; Fiellin, et al. 2011; Kakko, et al. 2003. If there is a role for medical cannabis in OUD management, it will be to augment rather than replace evidence-based pharmacologic treatment. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to advocate for the use of medical cannabis to manage OUD.

Medical Cannabis Formulations and Administration Methods Available in New York State

All medical cannabis products sold in dispensing facilities in New York State must meet specific manufacturing requirements regulated by the New York State Office of Cannabis Management. These requirements address methods for extracting cannabinoids from cannabis plants, the cannabinoid profile, the presence of additives, and labeling. All cannabis manufacturers must provide medical cannabis products that are equal parts delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) and low THC:high CBD (e.g., a 1:20 ratio of THC to CBD). All medical cannabis dispensing facilities also sell high THC and low CBD products, currently the most frequently used products by individuals in New York State. All products are tested by a laboratory located in New York State and licensed by the Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement to confirm cannabinoid content and identify contaminants NYSDOH 2020.

Medical cannabis administration methods available to individuals in New York State are summarized in Table 2, below. As of September 2021, the Commissioner of Health had approved metered liquid or oil preparations, solid and semi-solid preparations (capsules, chewable and effervescent tablets, lozenges), metered ground plant preparations, topical forms, and transdermal patches. In early October 2021, whole flower cannabis for vaporization was added as an approved form. The potential harms vary by administration method. Smoking ground flower through combustion—which is not currently legal in New York State—confers the highest risk of harm because of the high temperature of inhaled smoke and potential for chronic damage to bronchioles and airways Ribeiro and Ind 2018. Risk is lower when cannabis is vaporized rather than smoked via combustion. Table 2 outlines the advantages and disadvantages of each administration method.

References:

|

|||

| Table 2: Medical Cannabis Administration Methods Currently Available in New York State (as of January 2022) | |||

| Product, Method of Use, and Bioavailability | Bioavailability and Peak or Onset and Duration of Effect | Advantages | Disadvantages (also see guideline section Medical Cannabis Initiation) |

| Vaped oil: Inhaled using a battery-operated, portable pen-like device that administers a metered dose |

|

|

Potential for short- and long-term adverse effects:

|

| Vaped ground or whole flower: Inhaled using a tabletop or handheld device that creates vapor from the plant material and provides metered doses |

|

|

Potential for short- and long-term adverse effects:

|

| Capsule/tablets/chewable tablets/orally disintegrating tablets/effervescent tablets/dissolvable powder/chewable gels: Oral ingestion |

|

|

|

| Tincture and spray: Sublingual/oral |

|

|

|

| Suppository: Rectal |

|

|

|

| Lotions, gels: Transdermal |

|

|

|

Hemp-based CBD versus medical cannabis: The 2018 U.S. Farm Bill Act made it legal to develop, distribute, sell, and market CBD products derived from hemp plants, which contain less than 0.3% THC. The Farm Bill Act removed hemp-based CBD regulation from the purview of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Schedule I status (Schedule I drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with no medical purpose and a high potential for abuse). Hemp-based CBD has subsequently become available for purchase in retail settings, such as grocery and convenience stores, and with many different product types, including foods and beverages. Unregulated hemp-based CBD is often inaccurately labeled Vandrey, et al. 2008. One study found that almost half of products contained less CBD than the label described, and an additional quarter contained more CBD. In one-fifth of products sampled, THC was detected Bonn-Miller, et al. 2017.

Assessment

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Assessment

|

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; PEG, Pain, Enjoyment of Life, and General Activity. |

| Box 3: Good Practice for Medical Cannabis Assessment |

|

|

Abbreviations: CUDIT-R, Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; SUD, substance use disorder. |

Current amount and method of cannabis use: If patients are currently using medical, regulated adult-use, or unregulated cannabis, care providers should ask patients to describe their use in detail, including the amount and frequency of cannabis used daily, estimated delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) level, other cannabinoids (e.g., delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol) in consumed cannabis (if known), and the type and method of use. Details about a patient’s current pattern of cannabis use inform the recommended dose and type of medical cannabis and the recommended method for use.

If patients smoke cannabis, clinicians should ask about the method used, such as rolling papers, water pipe (bong), pipe, or vaporizer. Other methods include using cigar papers to roll a large “blunt” and smoking a combination of cannabis and tobacco, which may result in nicotine dependence and require nicotine replacement therapy if switching to a form of cannabis that does not include nicotine.

Regulated cannabis versus unregulated cannabis: Medical and regulated adult-use cannabis may be less harmful than unregulated cannabis because they have known THC and cannabidiol (CBD) content, are tested for potential contaminants, and can be purchased legally NYSDOH 2020. Regulated THC and CBD levels and ratios and doses in milligrams allow patients to titrate the dose of cannabis more precisely than is possible with unregulated cannabis. If a patient uses unregulated cannabis before initiating medical cannabis for a qualifying condition, a primary harm reduction goal may be to switch to medical cannabis. Clinicians can work with patients on limiting THC content and potentially harmful psychoactive effects while addressing symptoms of the presenting condition.

By acquiring medical cannabis at registered dispensing facilities, individuals can limit interactions with the street market and the criminal justice system. The criminalization of cannabis has a disproportionately negative effect on Black and Hispanic people; in New York State, in 2018, the arrest rate for cannabis possession was 2.6 times higher among Black people than White people, with rates ranging widely among counties ACLU 2020.

Conditions that require caution: Clinicians should determine if the patient seeking medical cannabis has a history of arrhythmia, CAD, or psychosis. Based primarily on limited evidence on the effects of THC, caution should be used when recommending medical cannabis treatment to patients with these conditions Athanassiou, et al. 2021; Skipina, et al. 2021; Yahud, et al. 2020; Goyal, et al. 2017; Shrivastava, et al. 2014. Acute THC exposure has been associated with tachycardia and developing or worsening psychosis Bryson and Frost 2011; Khiabani, et al. 2008; Sewell, et al. 2008. If arrhythmia, CAD, or psychosis is identified during evaluation for medical cannabis use and the patient is not being treated for the condition, refer the patient for treatment as appropriate. If the patient is already receiving treatment for the condition, consult with the treating clinician.

The following patient characteristics or conditions may affect the safety of medical cannabis treatment and should be carefully evaluated: personal history of substance use disorder (SUD), family history of schizophrenia Shrivastava, et al. 2014, personal history of hallucinations Shrivastava, et al. 2014, and risk factors for cardiac disease Goyal, et al. 2017. Safety concerns associated with these factors are based on limited evidence that acute THC exposure is associated with tachycardia and developing or worsening psychosis Bryson and Frost 2011; Khiabani, et al. 2008; Sewell, et al. 2008. History of SUD is considered a relative contraindication to medical cannabis because of concerns that individuals who use medical cannabis may be at increased risk for cannabis use disorder. However, in patients who are already using unregulated cannabis, medical cannabis certification could support harm reduction.

Cannabis use during pregnancy also warrants careful evaluation English, et al. 1997. Chronic THC exposure during pregnancy has been associated with preterm labor and intrauterine growth retardation Gunn, et al. 2016. For additional discussion of pregnancy, see the guideline section Medical Cannabis Initiation.

Potential drug-drug interactions: There is a paucity of evidence on potential drug-drug interactions with medical cannabis. THC and CBD are metabolized in the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system and may inhibit the metabolism of other strong CYP450 inhibitors, such as warfarin Damkier, et al. 2019; Alsherbiny and Li 2018. Cannabis can also have additive sedative effects when used with other sedating agents Echeverria-Villalobos, et al. 2019; Russo 2016. Cannabis and alcohol used in combination are associated with increased impairment of complex task performance, such as driving, compared with cannabis or alcohol use alone Miller, et al. 2020. To check for potential drug-drug interactions with medical cannabis, see Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment Monitoring Health Concerns Related to Marijuana: Drug Interaction Table.

Assess for qualifying conditions with standardized tools. Clinicians should assess the condition for which patients seek medical cannabis and other conditions that may be affected by cannabis treatment with standardized instruments at baseline and follow-up visits. Changes in test scores can indicate response to medical cannabis treatment and whether it is advisable to change dosage or formulation. Standardized tools include the PEG Scale Krebs, et al. 2009 and the DSM-5 PTSD Checklist Lang, et al. 2005.

Cost of medical cannabis: The typical cost of a 30-day supply of a starting dose of medical cannabis from a dispensary ranges from $70 to $150. Medical cannabis is not covered by insurance and must be paid for with cash or a debit card, which may pose significant barriers to access. Care providers should ensure that patients seeking medical cannabis certification are informed about cost and payment requirements.

Medical Cannabis Initiation

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Medical Cannabis Initiation

|

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; THC, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. |

Clinicians do not prescribe a specific formulation and dosage of cannabis; they recommend it. Clinicians can manage all aspects of medical cannabis treatment or limit their practice to assessment and certification and refer patients to dispensary pharmacists for all other related services (formulation, initial dosing, and dosing adjustments based on individual symptoms). Because clinicians have knowledge of or access to a patient’s medical history, comorbidities, and history of cannabis use, it is preferable for clinicians to direct formulation, initial dosing, and dosing adjustments for patients’ medical cannabis use and collaborate with the medical cannabis dispensary pharmacist as needed. If clinicians make specific recommendations in their certification, dispensary pharmacists are bound by law to follow those instructions (see New York State Medical Cannabis Program Patient Certification Instructions).

After clinician certification, patients must complete an online registration to link the certification to their state ID. If they do not have a state ID, they must send proof of residence to the NYSDOH. This is usually done electronically via the Medical Cannabis Data Management System. Patients with poor technological literacy may need assistance with this process.

Because of a lack of high-quality evidence, specific dosing regimens for the therapeutic use of medical cannabis are lacking. The authors have been managing patients with medical cannabis since 2016 when the Montefiore Medical Center Medical Cannabis Program was implemented. Boxes 4 and 5, below, outline basic strategies for implementing medical cannabis treatment based on the authors’ clinical experiences.

| Box 4: Good Practice for Implementation of Medical Cannabis Treatment [a] |

|

|

Abbreviations: CBD, cannabidiol; THC, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Note:

|

| Box 5: Sample Approach to Quantifying Current Cannabis Use and Determining Medical Cannabis Dose [a] |

|

|

Abbreviations: CBD, cannabidiol; THC, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Notes:

|

Initial dosage: For cannabis-naive patients, the lowest possible dose of 2.5 mg THC daily is recommended. For cannabis-experienced patients, clinicians should recommend an initial dose of 5 mg to 10 mg of total cannabinoids daily. For patients currently using cannabis, the overall goal is to reduce THC use and limit intoxication. After estimating the current daily dose of total cannabinoids and THC (see Box 4, above), clinicians should recommend an initial dose equivalent to at least 50% of the patient’s current daily amount of THC to minimize withdrawal symptoms, which may include irritability, sleeplessness, and decreased appetite Vandrey, et al. 2008.

Induction: Clinicians should advise patients to initiate medical cannabis at the lowest possible dose and slowly titrate up. Patients should take their initial dose at night and maintain that dose for 2 to 3 days. After that period, the dose can be increased by 2 mg to 5 mg THC daily. Patients can continue to increase the dose every 2 to 3 days until a therapeutic level is reached. If symptoms are experienced during the day, a midday or morning dose can be added. Clinicians should advise patients to maintain direct contact with pharmacists at the dispensary or with their certifying medical cannabis providers during the induction period to report any adverse events and address any dosing concerns.

Conditions that require caution in dosing and induction: Clinicians should use caution when recommending medical cannabis to patients with a known history of arrhythmia, CAD, or psychosis (see guideline section Assessment > Conditions that require caution). As with all patients initiating medical cannabis, clinicians should advise patients with these conditions to start at a low dose and increase their dose cautiously every 2 to 3 days.

Pregnancy: In patients who are pregnant or of childbearing potential, clinicians should discuss the risks of preterm labor and intrauterine growth restriction associated with cannabis use and advise against use of cannabis during pregnancy Gunn, et al. 2016. There is no evidence to support use of medical cannabis to manage pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting. In patients who are pregnant and who are not already using cannabis, clinicians should advise against initiating medical cannabis. In patients who are pregnant and using unregulated cannabis, clinicians and patients may find a harm reduction perspective useful. Patients may be using unregulated cannabis to treat specific symptoms such as PTSD, and medical cannabis may be the safer choice if a patient plans to continue using cannabis. For individuals who could become pregnant, clinicians should recommend the use of contraception while using medical cannabis.

Adverse effects: Clinicians should advise patients initiating medical cannabis to take the first dose at night to limit potential adverse effects, such as feeling high, dizzy, or unable to concentrate.

Severe adverse effects usually present as anxiety, paranoia, or panic attacks. Other neurologic symptoms include euphoria, lightheadedness, dizziness, or vertigo. In most cases, these symptoms require no intervention and are managed through observation. Rarely, cannabis can cause immediate nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain, which can be managed with symptomatic treatment such as antiemetics Noble, et al. 2019. To date, there are no known cases of fatal overdose from cannabis use Hasin 2018, but heavy cannabis use has been linked to increased healthcare utilization in states with legalized cannabis use, particularly among those using cannabis through oral rather than inhaled routes Monte, et al. 2019.

There is concern that cannabis intoxication will lead to motor vehicle accidents Brady and Li 2014. Cannabis use impairs driving in a dose-response manner Hartman and Huestis 2013. However, population-level studies have shown a mixed relationship between medical cannabis laws and increased motor vehicle accidents or traffic fatalities Rogeberg 2019; Santaella-Tenorio, et al. 2017; Dubois, et al. 2015; Pollini, et al. 2015; Masten and Guenzburger 2014; Blows, et al. 2005. Clinicians should caution patients about the potential for impaired driving while using cannabis and advise patients to avoid driving or operating heavy machinery if physical or mental control is diminished by cannabis use. Clinicians should emphasize that combining cannabis with alcohol can impair complex task performance, such as driving Miller, et al. 2020. It is also important to advise patients to store cannabis in a location that is safe from children and pets.

Follow-up: Individualized, ongoing follow-up is essential for support and modification of the treatment plan as indicated. Follow-up within 2 weeks of treatment initiation provides the opportunity to adjust a patient’s treatment plan based on initial experience. As treatment continues, the frequency of follow-up can be tailored to a patient’s specific needs and in accordance with the clinic’s existing policies regarding treatment and follow-up for patients taking other controlled substances. In the absence of an existing policy, this committee suggests clinical follow-up every 3 to 6 months.

Monitoring

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Monitoring

|

Abbreviations: CUD, cannabis use disorder; CUDIT-R, Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. |

At follow-up appointments, clinicians should ask patients about symptoms of potential adverse effects. Care providers should collaborate with patients’ existing treatment teams, including primary care providers, mental health care providers, cardiologists, and other specialists, to monitor these signs and symptoms. The most common adverse effects are described below.

In addition, clinicians should perform an annual assessment for CUD in all patients taking medical cannabis. If CUD is identified, clinicians should engage patients in shared decision-making to revise treatment goals as needed and develop a revised treatment plan to meet the new goals. The treatment plan should prioritize harm reduction and may include increased visits, using methods other than smoking, THC dose reduction, a modified dosing schedule, or linking patients to therapists or other mental health professionals Fischer, et al. 2017.

Psychiatric symptoms: Chronic cannabis use is associated with psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and psychosis, and has been linked to worsening schizophrenia in individuals with a preexisting genetic vulnerability Di Forti, et al. 2014; Caspi, et al. 2005; Patton, et al. 2002. However, a direct causal relationship is difficult to establish because multiple confounding factors blur the relationship between cannabis use and psychiatric illness. For example, individuals with anxiety or stress may be more likely to use cannabis Volkow, et al. 2014. Care providers should monitor patients for new or worsening psychiatric symptoms and discontinue medical cannabis if symptoms are identified. To decertify patients for medical cannabis use, see New York State Medical Cannabis Program Patient Certification Instructions.

Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome: A recent study reported that gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common cause for emergency room visits related to cannabis use Monte, et al. 2019. The most severe gastrointestinal effect of cannabis use, cannabis hyperemesis syndrome Allen, et al. 2004, manifests as cyclical nausea and vomiting and abdominal pain in individuals with chronic cannabis use. Symptoms may improve with hot showers or baths and resolve after cessation of cannabis use Schreck, et al. 2018. Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome has been described primarily in case series as early as 2004 Venkatesan, et al. 2019; Allen, et al. 2004; however, the criteria for diagnosing cannabis hyperemesis syndrome have been inconsistent, making it difficult to define the epidemiology. The most recent diagnostic criteria include: 1) episodic vomiting at least 3 times in the past year; 2) cannabis use for at least 1 year; 3) cannabis use at least 4 times per week on average; and 4) resolution of symptoms following a period of abstinence from cannabis use for at least 6 months or a period that spans at least 3 typical cyclical vomiting episodes for the individual Venkatesan, et al. 2019. Clinicians should monitor patients using medical cannabis for hyperemesis disorder symptoms; if symptoms are present, a trial of abstinence from cannabis may be appropriate.

Pulmonary effects: For patients who choose to vape, care providers should recommend avoidance of products purchased outside of registered facilities and, during follow-up visits, ask patients about any changes in breathing. Chronic inhaled cannabis use can lead to chronic bronchitis symptoms, including cough, sputum production, and wheezing Ribeiro and Ind 2018; Tashkin 2018. Cannabis use may result in pulmonary function test changes, but, unlike tobacco, cannabis has not been associated with chronic obstructive lung disease in observational studies Ribeiro and Ind 2018; Tashkin 2018. The mode of consumption could be related to specific types of respiratory syndromes.

A new lung disease associated with heavy vaping emerged in late 2019 Layden, et al. 2020; Schier, et al. 2019. To date, it remains unclear whether the risk is limited to specific types of vaping products or oils or with specific use patterns. It is suspected that vaping lung injury is caused by a severe inflammatory response to vitamin E acetate, an oil included in some formulations of vaporized products (including nicotine and cannabinoids). However, more studies are needed to confirm that vitamin E acetate is directly responsible for vaping lung injury Christiani 2020. No cases of vaping lung injury have been attributed to New York State medical cannabis vaped products.

Cannabis smoking may predispose individuals to pneumonia through damage of central airways and local immune response changes Shay, et al. 2003; Baldwin, et al. 1997; Fligiel, et al. 1997.

Smoked cannabis contains carcinogens, raising concerns about lung cancer risk. Observational studies show mixed findings: increased risk of lung cancer in all users of smoked cannabis Zhang, et al. 2015, only among heavy users Aldington, et al. 2008, and not at all Aldington, et al. 2008. These studies included potential confounders (e.g., tobacco use, environmental exposures) that may have skewed the results. Further research is needed to understand how individuals taking cannabis should be monitored for cancer.

Cognition: Cannabis intoxication has an acute effect on memory and attention, but the effect of cannabis use on long-term cognition has not been well studied Broyd, et al. 2016; Volkow, et al. 2016. Some case-control studies found that neuropsychological function was worse in participants who used unregulated cannabis than in controls with no use Schreiner and Dunn 2012; Grant, et al. 2003. However, in similar studies of individuals with at least 1 month of abstinence from unregulated cannabis, neuropsychological measures were similar in both groups Schreiner and Dunn 2012; Grant, et al. 2003. These findings suggest that any cognitive impairment due to cannabis use may be inversely related to the length of abstinence. In addition, longitudinal data from a small cohort of adult patients who use medical cannabis indicate improved executive function after 3 months. Medical cannabis could affect cognition differently than unregulated cannabis Gruber, et al. 2017

Among adolescents and young adults, whose brains are still developing, cannabis use is associated with changes in cognitive processes that could affect mental health, propensity toward future substance use disorders, and cognition Hurd, et al. 2019. As with adults, cognitive performance improves in adolescents after at least 25 days of abstinence from cannabis use Hurd, et al. 2019. There remains much to be understood about cannabis use and the developing brain. For additional information about the effects of cannabis use in adolescents and young adults, see the World Health Organization: The Health and Social Effects of Nonmedical Cannabis Use and the American Academy of Pediatrics: Counseling Parents and Teens About Marijuana Use in the Era of Legalization of Marijuana Ryan and Ammerman 2017; WHO 2016.

Cessation of medical cannabis: In patients with chronic cannabis use, abrupt cessation may lead to symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, which include, but are not limited to, irritability, anxiety, insomnia, depressed mood, strange dreams, headaches, and stomach pain Bonnet and Preuss 2017. Clinicians should inform patients who want to stop using cannabis about the risk of cannabis withdrawal symptoms. Treatment of cannabis withdrawal symptoms is not well studied, but symptoms may be managed with, for instance, zolpidem for insomnia or benzodiazepines for anxiety Brezing and Levin 2018. Few data exist on the effects of tapering the cannabis, but individuals may experience fewer withdrawal symptoms with a gradual reduction in dose rather than an abrupt stop. Clinicians should discuss these factors with the patient and, if requested, help develop a tapering plan. To decertify patients for medical cannabis use, see New York State Medical Cannabis Program Patient Certification Instructions.

Appendix: Office of Cannabis Management (OCM) Communications

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: THERAPEUTIC USE OF MEDICAL CANNABIS IN NEW YORK STATE |

Assessment

Medical Cannabis Initiation

Monitoring

|

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CUD, cannabis use disorder; CUDIT-R, Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; PEG, Pain, Enjoyment of Life, and General Activity; THC, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. |

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

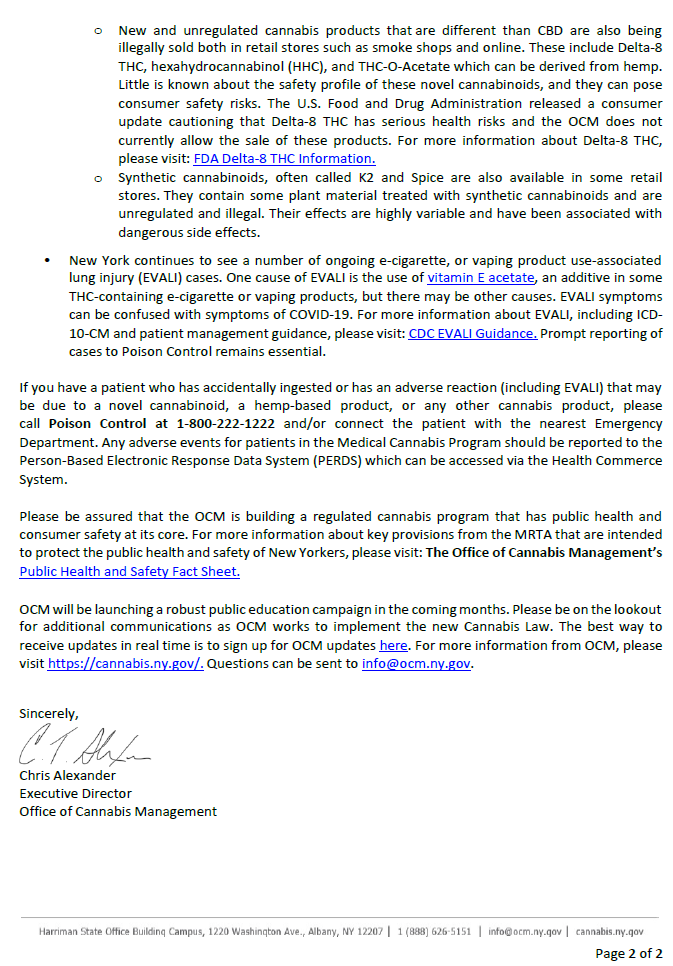

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

ACLU. A tale of two countries: racially targeted arrests in the era of marijuana reform. 2020 Mar 23. https://www.aclu.org/report/tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

Aldington S., Harwood M., Cox B., et al. Cannabis use and risk of lung cancer: a case-control study. Eur Respir J 2008;31(2):280-86. [PMID: 18238947]

Allen J. H., de Moore G. M., Heddle R., et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut 2004;53(11):1566-70. [PMID: 15479672]

Allendorfer J. B., Nenert R., Bebin E. M., et al. fMRI study of cannabidiol-induced changes in attention control in treatment-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2019;96:114-21. [PMID: 31129526]

Alsherbiny M. A., Li C. G. Medicinal cannabis-potential drug interactions. Medicines (Basel) 2018;6(1). [PMID: 30583596]

Ansari N. N., Naghdi S., Moammeri H., et al. Ashworth Scales are unreliable for the assessment of muscle spasticity. Physiother Theory Pract 2006;22(3):119-25. [PMID: 16848350]

Athanassiou M., Dumais A., Gnanhoue G., et al. A systematic review of longitudinal studies investigating the impact of cannabis use in patients with psychotic disorders. Expert Rev Neurother 2021;21(7):779-91. [PMID: 34120548]

Bachhuber M. A., Saloner B., Cunningham C. O., et al. Medical cannabis laws and opioid analgesic overdose mortality in the United States, 1999-2010. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(10):1668-73. [PMID: 25154332]

Baldwin G. C., Tashkin D. P., Buckley D. M., et al. Marijuana and cocaine impair alveolar macrophage function and cytokine production. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156(5):1606-13. [PMID: 9372683]

Bar-Sela G., Zalman D., Semenysty V., et al. The effects of dosage-controlled cannabis capsules on cancer-related cachexia and anorexia syndrome in advanced cancer patients: pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther 2019;18:1534735419881498. [PMID: 31595793]

Ben-Shabat S., Hanus L. O., Katzavian G., et al. New cannabidiol derivatives: synthesis, binding to cannabinoid receptor, and evaluation of their antiinflammatory activity. J Med Chem 2006;49(3):1113-17. [PMID: 16451075]

Blows S., Ivers R. Q., Connor J., et al. Marijuana use and car crash injury. Addiction 2005;100(5):605-11. [PMID: 15847617]

Boehnke K. F., Litinas E., Clauw D. J. Medical cannabis use is associated with decreased opiate medication use in a retrospective cross-sectional survey of patients with chronic pain. J Pain 2016;17(6):739-44. [PMID: 27001005]

Bonn-Miller M. O., Loflin M. J. E., Thomas B. F., et al. Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA 2017;318(17):1708-9. [PMID: 29114823]

Bonnet U., Preuss U. W. The cannabis withdrawal syndrome: current insights. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2017;8:9-37. [PMID: 28490916]

Bradford A. C., Bradford W. D. Medical marijuana laws may be associated with a decline in the number of prescriptions for medicaid enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(5):945-51. [PMID: 28424215]

Bradford A. C., Bradford W. D., Abraham A., et al. Association between US state medical cannabis laws and opioid prescribing in the Medicare part D population. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(5):667-72. [PMID: 29610897]

Brady J. E., Li G. Trends in alcohol and other drugs detected in fatally injured drivers in the United States, 1999-2010. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179(6):692-99. [PMID: 24477748]

Brezing C. A., Levin F. R. The current state of pharmacological treatments for cannabis use disorder and withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018;43(1):173-94. [PMID: 28875989]

Broyd S. J., van Hell H. H., Beale C., et al. Acute and chronic effects of cannabinoids on human cognition-a systematic review. Biol Psychiatry 2016;79(7):557-67. [PMID: 26858214]

Bryson E. O., Frost E. A. The perioperative implications of tobacco, marijuana, and other inhaled toxins. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2011;49(1):103-18. [PMID: 21239908]

Cameron C., Watson D., Robinson J. Use of a synthetic cannabinoid in a correctional population for posttraumatic stress disorder-related insomnia and nightmares, chronic pain, harm reduction, and other indications: a retrospective evaluation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;34(5):559-64. [PMID: 24987795]

Caputi T. L., Humphreys K. Medical marijuana users are more likely to use prescription drugs medically and nonmedically. J Addict Med 2018;12(4):295-99. [PMID: 29664895]

Caspi A., Moffitt T. E., Cannon M., et al. Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(10):1117-27. [PMID: 15866551]

Christiani D. C. Vaping-induced acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2020;382(10):960-62. [PMID: 31491071]

Compton W. M., Han B., Jones C. M., et al. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3(10):954-64. [PMID: 27592339]

Damkier P., Lassen D., Christensen M. M. H., et al. Interaction between warfarin and cannabis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2019;124(1):28-31. [PMID: 30326170]

DEA. Department of Justice/Drug Enforcement Administration drug fact sheet: marijuana/cannabis. 2020 Apr. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Marijuana-Cannabis-2020.pdf [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

Devinsky O., Cross J. H., Laux L., et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017;376(21):2011-20. [PMID: 28538134]

Devinsky O., Patel A. D., Cross J. H., et al. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018;378(20):1888-97. [PMID: 29768152]

Di Forti M., Sallis H., Allegri F., et al. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull 2014;40(6):1509-17. [PMID: 24345517]

Dubois S., Mullen N., Weaver B., et al. The combined effects of alcohol and cannabis on driving: impact on crash risk. Forensic Sci Int 2015;248:94-100. [PMID: 25612879]

Echeverria-Villalobos M., Todeschini A. B., Stoicea N., et al. Perioperative care of cannabis users: a comprehensive review of pharmacological and anesthetic considerations. J Clin Anesth 2019;57:41-49. [PMID: 30852326]

ElSohly M. A., Mehmedic Z., Foster S., et al. Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995-2014): analysis of current data in the United States. Biol Psychiatry 2016;79(7):613-19. [PMID: 26903403]

ElSohly(a) M. A., Stanford D. F., Harland E. C., et al. Rectal bioavailability of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol from the hemisuccinate ester in monkeys. J Pharm Sci 1991;80(10):942-45. [PMID: 1664466]

ElSohly(b) M. A., Little T. L., Hikal A., et al. Rectal bioavailability of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol from various esters. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1991;40(3):497-502. [PMID: 1666913]

English D. R., Hulse G. K., Milne E., et al. Maternal cannabis use and birth weight: a meta-analysis. Addiction 1997;92(11):1553-60. [PMID: 9519497]

FDA. Cesamet (nabilone) capsules for oral administration. 2006 May. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/018677s011lbl.pdf [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

FDA. Marinol (dronabinol) capsules, for oral use. 2017 Aug. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018651s029lbl.pdf [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

FDA. FDA and cannabis: research and drug approval process. 2020 Oct 1. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

FDA(a). FDA approves first drug comprised of an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy. 2018 Jun 25. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-comprised-active-ingredient-derived-marijuana-treat-rare-severe-forms [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

FDA(b). Epidiolex (cannabidiol) oral solution. 2018 Jun. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210365lbl.pdf [accessed 2021 Nov 9]

Fiellin D. A., Weiss L., Botsko M., et al. Drug treatment outcomes among HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;56 Suppl 1(0 1):s33-38. [PMID: 21317592]

Fischer B., Russell C., Sabioni P., et al. Lower-risk cannabis use guidelines: a comprehensive update of evidence and recommendations. Am J Public Health 2017;107(8):e1-e12. [PMID: 28644037]

Fligiel S. E., Roth M. D., Kleerup E. C., et al. Tracheobronchial histopathology in habitual smokers of cocaine, marijuana, and/or tobacco. Chest 1997;112(2):319-26. [PMID: 9266864]

Fraser G. A. The use of a synthetic cannabinoid in the management of treatment-resistant nightmares in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). CNS Neurosci Ther 2009;15(1):84-88. [PMID: 19228182]

Goodwin R. S., Gustafson R. A., Barnes A., et al. Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, 11-hydroxy-delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol in human plasma after controlled oral administration of cannabinoids. Ther Drug Monit 2006;28(4):545-51. [PMID: 16885723]

Goyal H., Awad H. H., Ghali J. K. Role of cannabis in cardiovascular disorders. J Thorac Dis 2017;9(7):2079-92. [PMID: 28840009]

Grant I., Gonzalez R., Carey C. L., et al. Non-acute (residual) neurocognitive effects of cannabis use: a meta-analytic study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2003;9(5):679-89. [PMID: 12901774]

Grotenhermen F., Müller-Vahl K. The therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012;109(29-30):495-501. [PMID: 23008748]

Gruber S. A., Sagar K. A., Dahlgren M. K., et al. The grass might be greener: medical marijuana patients exhibit altered brain activity and improved executive function after 3 months of treatment. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:983. [PMID: 29387010]

Gunn J. K., Rosales C. B., Center K. E., et al. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6(4):e009986. [PMID: 27048634]

Gustafson R. A., Moolchan E. T., Barnes A., et al. Validated method for the simultaneous determination of Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-hydroxy-THC and 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC in human plasma using solid phase extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with positive chemical ionization. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2003;798(1):145-54. [PMID: 14630369]

Guy G. W., Robson P. J. A phase I, open label, four-way crossover study to compare the pharmacokinetic profiles of a single dose of 20 mg of a cannabis based medicine extract (CBME) administered on 3 different areas of the buccal mucosa and to investigate the pharmacokinetics of CBME per oral in healthy male and female volunteers (GWPK0112). J Cannabis Ther 2004;3(4):79-120. https://doi.org/10.1300/J175v03n04_01

Hartman R. L., Huestis M. A. Cannabis effects on driving skills. Clin Chem 2013;59(3):478-92. [PMID: 23220273]

Hasin D. S. US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018;43(1):195-212. [PMID: 28853439]

Hilliard A., Stott C., Wright S., et al. Evaluation of the effects of sativex (THC BDS: CBD BDS) on inhibition of spasticity in a chronic relapsing experimental allergic autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a model of multiple sclerosis. ISRN Neurol 2012;2012:802649. [PMID: 22928118]

Hser Y. I., Evans E., Huang D., et al. Long-term outcomes after randomization to buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction 2016;111(4):695-705. [PMID: 26599131]

Huestis M. A. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodivers 2007;4(8):1770-1804. [PMID: 17712819]

Huestis M. A., Sampson A. H., Holicky B. J., et al. Characterization of the absorption phase of marijuana smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992;52(1):31-41. [PMID: 1320536]

Hurd Y. L., Manzoni O. J., Pletnikov M. V., et al. Cannabis and the developing brain: insights into its long-lasting effects. J Neurosci 2019;39(42):8250-58. [PMID: 31619494]

Jetly R., Heber A., Fraser G., et al. The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: A preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;51:585-88. [PMID: 25467221]

Kakko J., Svanborg K. D., Kreek M. J., et al. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361(9358):662-68. [PMID: 12606177]

Karschner E. L., Darwin W. D., Goodwin R. S., et al. Plasma cannabinoid pharmacokinetics following controlled oral delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and oromucosal cannabis extract administration. Clin Chem 2011;57(1):66-75. [PMID: 21078841]

Khiabani H. Z., Mørland J., Bramness J. G. Frequency and irregularity of heart rate in drivers suspected of driving under the influence of cannabis. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19(8):608-12. [PMID: 19046727]

Krebs E. E., Lorenz K. A., Bair M. J., et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(6):733-38. [PMID: 19418100]

Lang E. V., Hatsiopoulou O., Koch T., et al. Can words hurt? Patient-provider interactions during invasive procedures. Pain 2005;114(1-2):303-9. [PMID: 15733657]

Layden J. E., Ghinai I., Pray I., et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin - final report. N Engl J Med 2020;382(10):903-16. [PMID: 31491072]

Lowe D. J. E., Sasiadek J. D., Coles A. S., et al. Cannabis and mental illness: a review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019;269(1):107-20. [PMID: 30564886]

Mackie K. Distribution of cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2005;(168):299-325. [PMID: 16596779]

Maione S., Piscitelli F., Gatta L., et al. Non-psychoactive cannabinoids modulate the descending pathway of antinociception in anaesthetized rats through several mechanisms of action. Br J Pharmacol 2011;162(3):584-96. [PMID: 20942863]

Mancher M., Leshner A. I. Medications for opioid use disorder save lives; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538936/

Masten S. V., Guenzburger G. V. Changes in driver cannabinoid prevalence in 12 U.S. states after implementing medical marijuana laws. J Safety Res 2014;50:35-52. [PMID: 25142359]

Matsuda L. A., Lolait S. J., Brownstein M. J., et al. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 1990;346(6284):561-64. [PMID: 2165569]

Mattes R. D., Shaw L. M., Edling-Owens J., et al. Bypassing the first-pass effect for the therapeutic use of cannabinoids. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1993;44(3):745-47. [PMID: 8383856]

Mattick R. P., Breen C., Kimber J., et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(2):CD002207. [PMID: 24500948]

Miller R. E., Brown T. L., Lee S., et al. Impact of cannabis and low alcohol concentration on divided attention tasks during driving. Traffic Inj Prev 2020;21(Suppl 1):s123-29. [PMID: 33035082]

Monte A. A., Shelton S. K., Mills E., et al. Acute illness associated with cannabis use, by route of exposure: an observational study. Ann Intern Med 2019;170(8):531-37. [PMID: 30909297]

Monte A. A., Zane R. D., Heard K. J. The implications of marijuana legalization in Colorado. JAMA 2015;313(3):241-42. [PMID: 25486283]

Munro S., Thomas K. L., Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 1993;365(6441):61-65. [PMID: 7689702]

National Academies of Sciences. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research; 2017. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28182367/