Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: February 2, 2024

Lead author: Tiffany Lu, MD, MS

Writing group: Susan D. Whitley, MD; Timothy J. Wiegand, MD; Sharon L. Stancliff, MD; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Substance Use Guidelines Committee

Date of original publication: August 29, 2019

This guideline was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to inform clinicians who do not specialize in substance use treatment of the currently available and effective strategies for treating adult patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). With this guideline, the NYSDOH AI aims to:

- Assist clinicians in engaging with patients about OUD treatment goals, including overdose prevention.

- Provide up-to-date information about available OUD treatment options and their use.

- Provide clinical recommendations for the use of buprenorphine/naloxone to treat OUD in the nonspecialty setting.

- Increase the availability of nonspecialty treatment for adults with OUD.

- Promote a harm reduction approach to the treatment of all substance use disorders (SUDs), which involves practical strategies and ideas for reducing the negative consequences associated with substance use.

Goals of OUD Treatment

The United States is in the midst of an unprecedented opioid crisis, with dramatic increases observed in opioid use, OUD, and opioid-related overdose deaths SAMHSA(a) 2021; Scholl, et al. 2018; Rudd, et al. 2016. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show an estimated 75,673 opioid-related overdose deaths in the 12 months ending in April 2021, an increase from the estimated 56,064 deaths in the prior year CDC(b) 2021.

The rapid rise in opioid-related overdose deaths in recent years is driven by greatly increased exposure to illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogues. Since 2014, these high-potency synthetic opioids have been spreading in the illicit drug supply, often as adulterated or substituted heroin or pressed into counterfeit pills Ciccarone 2021. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogues currently account for more than 80% of opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States, increasing from a rate of 11.4 per 100,000 population in 2019 to 17.8 per 100,000 population in 2020 CDC(a) 2021. Additionally, other synthetic additives such as xylazine, a veterinary sedative, have been found with increasing frequency in the drug supply and have contributed to increases in morbidity and mortality Gupta, et al. 2023; Alexander, et al. 2022; Korn, et al. 2021. As of March 2023, fentanyl mixed with xylazine had been found in drugs confiscated in 48 states; the estimated number of drug-poisoning deaths in the United States involving xylazine increased from 260 in 2018 to 3,480 in 2021 Gupta, et al. 2023.

Currently, 3 pharmacologic OUD treatment options are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration: methadone, BUP, and extended-release (XR) naltrexone. Although pharmacologic treatment of OUD reduces overdose mortality by nearly 50%, only 1 out of 5 Americans with past-year OUD had received life-saving treatment in 2021, the most recent year for which data are available Jones(b), et al. 2023; Krawczyk, et al. 2022; Larochelle, et al. 2018; Sordo, et al. 2017. Increased access and linkage to evidence-based OUD treatment is urgently needed given the opioid epidemic’s continued toll on individuals, families, and communities. Implementing and scaling up effective OUD treatment across diverse settings is critical to curbing the opioid epidemic CDC 2022.

Harm reduction as a treatment goal: A traditional goal of OUD treatment is abstinence or long-term cessation of opioid use. However, as fentanyl-fueled overdose deaths increase, harm reduction, including survival, has become an important goal. The mortality benefit of receiving medications for OUD remains strong even if a person intermittently uses opioids during treatment Stone, et al. 2020. In addition, abstinence may take time to achieve and may not be a realistic goal for all individuals. Other goals that can lead to substantial improvements in the health and lives of people with OUD and reduce harm include:

- Reducing the frequency and quantity of opioid use

- Reducing the risk and occurrence of overdose

- Staying engaged in care, which can facilitate prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of other medical and mental health conditions

- Reducing high-risk behaviors, such as injection drug use and sharing of injection equipment, and reducing related complications, such as infection

- Improving quality of life and other social indicators, such as employment and stable housing, and reducing the risk of incarceration

For more information, see NYSDOH AI guideline Substance Use Harm Reduction in Medical Care.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Role of and Requirements for Clinicians

Primary care clinicians in New York State can play an essential role in identifying and treating OUD in their patients. Pharmacologic treatment for OUD in primary care settings reduces nonprescription opioid use and improves retention in treatment Alford, et al. 2011; Altice, et al. 2011; Fiellin, et al. 2011; Lucas, et al. 2010; Cunningham, et al. 2008; Magura, et al. 2007; Mintzer, et al. 2007; Samet, et al. 2001. One study examining BUP treatment for OUD in “real-world” primary care settings reported a 12-month retention rate of 74% among participants treated in a primary care clinic and 49% among those referred to OUD treatment outside of the primary care clinic Lucas, et al. 2010. In addition, a study among individuals with HIV demonstrated that retention in primary care-based BUP treatment is associated with the initiation of antiretroviral therapy and improved viral load suppression Altice, et al. 2011. Similarly, a study among individuals with hepatitis C virus (HCV) reported that retention in primary care-based BUP treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of being evaluated and offered treatment for HCV infection Norton, et al. 2017.

In light of the opioid crisis, all clinicians in New York State, including those who deliver primary care, should be informed about risk reduction and treatment options for OUD.

Federal requirements for clinicians: Federal policies regulate OUD treatment based on the assigned controlled substance classification under the U.S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Buprenorphine is a schedule III-controlled substance that has been subject to evolving restrictions. Until 2022, physicians and advanced clinical specialists were required to apply for a separate DEA waiver (commonly known as the “DATA-waiver” or “X-waiver”) to prescribe any formulation of BUP for OUD. In January 2023, the Consolidated Appropriations Act (also known as the Omnibus bill) removed the federal requirement for a DEA waiver to prescribe BUP (see DEA letter on DATA-Waiver Program). With this provision, all clinicians who have a current DEA license to prescribe schedule III-controlled substances can now prescribe BUP for OUD without a patient limit. Effective June 2023, all clinicians who obtain or renew their DEA license will be required to complete 8 hours of training related to substance use (see DEA letter on training requirement). The effect of these policy changes will have to be assessed; however, the elimination of prescriber restrictions is anticipated to increase access to BUP treatment.

In contrast, methadone is a schedule II-controlled substance that can only be dispensed or administered for OUD treatment in specialty opioid treatment programs certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and single-state agencies for substance use services. Oral naltrexone and XR naltrexone are not scheduled substances and can be prescribed without clinician restrictions.

All 3 medications (BUP, methadone, and naltrexone) can be administered in any acute care setting, although restrictions apply for methadone (see DEA: Narcotic Treatment Program Manual: A Guide to DEA Narcotic Treatment Program Regulations).

Legal Protections for Individuals With OUD

The New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL) and the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) protect individuals with disabilities from discrimination. Under the NYSHRL and ADA, individuals taking prescribed medical treatment for OUD and those in recovery from OUD are considered disabled (see The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Opioid Crisis: Combating Discrimination Against People in Treatment or Recovery). The NYSHRL and the ADA exclude from protection individuals who are currently using illegal drugs.

Employers and housing providers are prohibited from discriminating against individuals with disabilities under the NYSHRL. Employers are prohibited from denying a job opportunity to a qualified individual, terminating an employee because of a disability, and making inquiries about an individual’s disability, which includes questions about prescribed medical care for OUD. Employers are required to provide reasonable accommodations to assist disabled people in performing their job functions. It is unlawful for housing providers, including skilled nursing facilities, to refuse to house or discriminate against a tenant because they are taking medical treatment for OUD or are in recovery from OUD.

Information about these protections and enforcement of the NYSHRL can be found at the New York State Division of Human Rights.

Telehealth

Telehealth has the potential to reduce barriers to care for individuals with OUD. Historically, under the Ryan Haight Act of 2008, at least 1 in-person medical evaluation of a patient was required before prescribing controlled substances, including BUP. However, at the start of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE), the DEA and SAMHSA issued exemptions to allow for BUP initiation through telehealth, including telephonic (audio-only) and video (audio-visual) visits, without first requiring an in-person visit SAMHSA 2020. Practitioners must still adhere to state-specific requirements for telehealth (see NYSDOH Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement). In New York State, both telephonic and video visits for initiating BUP were covered under Medicaid during the COVID-19 PHE NYSDOH 2023; Chan, et al. 2022; Cunningham, et al. 2022. In-person medical evaluation is still required to initiate methadone treatment. The long-term ability to initiate medication for OUD treatment via telehealth remains unclear at this time; PHE exemptions for telehealth have been extended through 2024 while new regulations are under review.

To date, observational studies have found that BUP treatment delivered through telehealth is associated with similar or improved treatment retention and reduced overdose risk compared with BUP treatment delivered through in-person visits Jones(a), et al. 2023; Chan, et al. 2022; Cunningham, et al. 2022; Jones, et al. 2022. Telehealth BUP treatment is feasible and effective for providing OUD treatment for patients who may have limited or no access to in-person clinical care, including patients who live in remote locations, are not stably housed, or are incarcerated Williams, et al. 2023; Tofighi, et al. 2022; Belcher, et al. 2021; Weintraub, et al. 2021. However, rigorous evaluation of telehealth-delivered BUP treatment is still needed to evaluate long-term treatment outcomes, address disparities in access, and implement best practices. Adults who are older, have low income, have limited English language proficiency, are members of ethnic or racial minorities, or who reside in areas with limited or no internet access may not be able to access telehealth services NEJM Catalyst 2020. Access to video visits may also be challenging among people who use drugs who do not have electronic devices, internet or mobile data access, or privacy.

In-person visits for new patients may help establish rapport and facilitate assessment of medical or mental health needs beyond OUD treatment and can be arranged according to an expected timeframe (e.g., within 2 to 4 weeks) without delaying OUD treatment initiation. To ensure treatment access equity, in-person visits should be prioritized for patients who prefer in-person visits or have clinical needs that may benefit from an in-person evaluation (e.g., recent overdose or other acute complications related to OUD, co-occurring SUDs that may increase overdose risk, unstable medical or mental health conditions, persistent concern for diversion). Treatment should not be withheld solely based on patient preference for telehealth or in-person visits.

Treatment Considerations

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Overdose Prevention

Who to Treat

Treatment Options

|

Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; ED, emergency department; NLX, naloxone; OUD, opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder; XR, extended-release. Notes:

|

Overdose Prevention

An essential part of initiating and continuing OUD treatment is overdose prevention counseling. Counsel patients to:

- Assume all illicitly manufactured opioids will contain fentanyl or other high-potency synthetic opioids, and that stimulants and counterfeit pills may contain these agents.

- When possible, test drugs with fentanyl test strips, xylazine test strips, or other drug-checking equipment. Online sources include MATTERS (for New York State residents and programs, no charge), DanceSafe, and BTNX. Some NYS Authorized Syringe Exchange Sites may provide fentanyl test strips and other drug-checking systems.

- Try not to use drugs alone. Arrange for someone to check in; use phone- and web-based apps (e.g., Never Use Alone Inc. at 800-484-3731).

- When using any drug, start with a small amount.

- Carry NLX, learn how to use it, and encourage friends and contacts to do the same. The 4 mg NLX nasal spray formulation is available at pharmacies, at NYSDOH-Registered Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs (no charge), and online through NEXT Distro. NLX is covered by New York State Medicaid and most private insurers.

In addition to overdose prevention counseling, clinicians should incorporate harm reduction into OUD treatment planning. For example, all patients who inject opioids or other drugs should be counseled on use of sterile needles and syringes. Licensed pharmacies, healthcare facilities, and clinicians can furnish hypodermic needles or syringes to individuals ≥18 years old without a patient-specific prescription; drug equipment is also available at NYS Authorized Syringe Exchange Sites.

Who to Treat

SUDs, including OUD, have become widely recognized as chronic conditions McLellan, et al. 2014. OUD is associated with significant and persistent changes in brain structure and function. Naturally occurring endogenous opioids in the brain act on opioid receptors to produce effects on cognition, emotion, pain, sleep, and other domains Maldonado 2010. With repeated exposure to external (exogenous) opioids, the brain’s opioid system may no longer be able to self-regulate Volkow, et al. 2019; Volkow and Koob 2015. When this occurs, tolerance to opioids develops, the brain produces lower levels of endogenous opioids, and a larger dose of exogenous opioids is required to obtain the same effects Volkow, et al. 2016; Williams, et al. 2013. In addition, physical withdrawal symptoms can develop within hours of discontinuing or reducing opioid use Kampman and Jarvis 2015.

Clinicians should offer pharmacologic treatment to adult patients diagnosed with OUD, including patients who are not actively using opioids (see Box 1, below). Pharmacologic treatment is essential in stabilizing and restoring chronic changes in brain structure and function. By alleviating opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms, pharmacologic treatment can also help individuals focus on improving behavioral components of OUD.

Pharmacologic treatment should be offered to individuals diagnosed with OUD who are not actively using opioids but who are at risk of resuming opioid use. Two important risk factors for return to use and overdose among individuals with OUD are a history of overdose and leaving a controlled setting, such as prison, jail, hospital, or other treatment facilities Olfson, et al. 2018; Binswanger, et al. 2013. Medical care, including hepatitis C virus and HIV screening, prevention, and treatment, as indicated, should be offered to individuals with OUD regardless of whether they are engaged in OUD treatment.

| Box 1: DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Opioid Use Disorder [a] |

|

The DSM-5 describes OUD as a pattern of opioid use that leads to problems or distress, with at least 2 of the criteria below occurring within 12 months. Severity of the OUD is determined by the number of criteria met: mild (2 to 3 criteria); moderate (4 to 5 criteria); and severe (≥6 criteria).

|

|

Abbreviations: DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th edition; OUD, opioid use disorder. Notes:

|

Use of other substances: Individuals should not be excluded from pharmacologic OUD treatment based on their use of other substances unless there are contraindications to the OUD medications and the risks outweigh the consequences of untreated OUD Payne, et al. 2019; Cunningham(a), et al. 2013; Sullivan, et al. 2011. Studies have demonstrated no significant differences in OUD treatment retention or self-reported opioid use in participants with OUD who used cocaine during the study compared with those who did not Cunningham(a), et al. 2013; Sullivan, et al. 2011. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Drug Safety Communication in 2017 urging caution in withholding methadone or BUP from patients using benzodiazepines or alcohol, noting that the harm of not treating OUD outweighs the risk of adverse events associated with combining the medication. Co-occurring substance use may influence individual treatment plans but should not be the sole reason for excluding patients from pharmacologic OUD treatment.

Psychosocial treatment: Psychosocial treatment interventions for OUD can be useful adjuncts to pharmacologic treatment for some patients; however, clinical trial results have consistently demonstrated that pharmacologic treatment is more effective than nonpharmacologic treatment of OUD in reducing nonprescription opioid use, decreasing overdose risk, improving retention in care, and improving other psychosocial and medical conditions Wakeman, et al. 2020; Fiellin, et al. 2013; Ruetsch, et al. 2012; Tetrault, et al. 2012; Amato(a), et al. 2011; Amato(b), et al. 2011; Weiss, et al. 2011; Humphreys, et al. 2004. A lack of participation in structured psychosocial treatment for OUD should not prompt clinicians to withhold or discontinue pharmacologic treatment for OUD. When psychosocial treatment is mandated by the criminal justice system, child welfare, or other agencies, a clinician’s primary responsibility is to maintain the therapeutic alliance and partner with the patient to address legal mandates.

OUD treatment initiation in the ED: Clinicians in EDs and inpatient hospital settings have many opportunities to reach individuals with OUD who are not linked to care. Clinicians should initiate pharmacologic OUD treatment in patients who have been treated for an opioid overdose or a complication related to opioid use before they are discharged from acute care and refer patients for OUD treatment. Clinicians in these settings should also dispense or prescribe NLX for patients who use opioids. Studies have demonstrated that initiating BUP treatment in the ED is feasible and cost-effective and can contribute to increased retention in care Wakeman, et al. 2021; Englander, et al. 2019; Busch, et al. 2017; D'Onofrio, et al. 2017; D'Onofrio, et al. 2015; Liebschutz, et al. 2014. The NYSDOH supports MATTERS, an online platform for clinicians in acute care settings to facilitate linkage to care. For further guidance on providing BUP treatment in EDs and hospital settings, please see:

- American College of Emergency Physicians: Consensus Recommendations on the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in the Emergency Department

- Society of Hospital Medicine: Management of Opioid Use Disorder and Associated Conditions Among Hospitalized Adults

Treatment Options

OUD treatment history: Clinicians should obtain a complete history of previous OUD treatment to ensure that the patient’s experiences, preferences, and needs are incorporated into treatment decision-making. When asking patients about prior pharmacologic treatment, clinicians should inquire about tolerance of and success with medication initiation, experience with long-term treatment, adherence challenges, adverse effects, treatment duration, and reasons for stopping treatment SAMHSA(b) 2021; ASAM 2020. Prior experiences with pharmacologic treatment often shape preferences for specific medications; patients who have had negative experiences with 1 medication may prefer to try another Yarborough, et al. 2016. Clinicians should also inquire about self-treatment with nonprescribed medications (including BUP), which is prevalent among individuals trying to reduce opioid use or struggling to access, engage in, or stay engaged in treatment. In observational studies, prior use of nonprescribed BUP is associated with improved treatment retention Williams, et al. 2022; Monico, et al. 2015; Cunningham(b), et al. 2013.

Available pharmacologic treatment: Clinicians should inform patients with OUD about all available pharmacologic treatment options and formulations and engage in shared decision-making about the best setting, medication, and formulation based on the individual patient’s treatment goals, preferences, and insurance coverage.

Currently, 3 medications are approved by the FDA for OUD treatment: methadone, BUP, and XR naltrexone. All 3 medications act on the mu-opioid receptor: methadone as a full opioid agonist, BUP as a partial opioid agonist, and naltrexone as an opioid antagonist. The preferred agents for treatment of OUD are BUP and methadone. Decades of clinical research support the efficacy of opioid agonist medications in reducing nonprescription opioid use and improving retention in treatment among individuals with OUD. BUP and methadone are both associated with up to 50% reduction in risk of all-cause and overdose-related mortality Mattick, et al. 2014; Minozzi, et al. 2011; Ling and Wesson 2003; Mello and Mendelson 1980; Dole and Nyswander 1965. Methadone is associated with higher rates of long-term treatment retention than BUP Degenhardt, et al. 2023, but BUP is more widely available than methadone. Treatment planning, therefore, requires consideration of the relative differences in long-term treatment retention along with a patient’s previous experience, access, and preferences. For a discussion of each medication, see the guideline sections Buprenorphine/Naloxone, Methadone, and Naltrexone.

Many individuals with OUD achieve their treatment goals in outpatient primary care-based settings. When available, specialty OUD treatment settings (e.g., outpatient treatment programs, opioid treatment programs [OTPs]) that provide pharmacologic treatment along with frequent visits, individual and group counseling, and other supportive services may benefit some individuals, including those with co-occurring SUDs, mental health needs requiring intensive treatment, or inadequate psychosocial supports.

Treatment selection based on individual factors: Many individual patient factors influence OUD treatment choice, including prior treatment experience, ease of access, and preferences (see Table 1, below). Pharmacologically, 2 key factors are the patient’s opioid tolerance and co-occurring medical conditions. Patients with low opioid tolerance who wish to initiate opioid agonist treatment may benefit from BUP rather than methadone because, as a partial opioid agonist, BUP carries a lower risk for sedation. Methadone is associated with QT prolongation and respiratory depression, so may not be preferred for patients with cardiac conduction disorders or severe respiratory conditions FDA 2014.

Although many individuals with OUD can be treated with BUP/NLX in the primary care setting, some have clinical challenges that warrant consultation with experts in addiction medicine, obstetrics, adolescent care, pain management, and other medical specialties. Consultation may be necessary when, for instance, managing the care of patients with chronic pain or patients who have ongoing nonprescription opioid use or cravings despite taking the maximum FDA-approved dose (BUP/NLX 24 mg/6 mg daily). Doses of BUP up to 32 mg daily may be indicated to relieve opioid craving and promote treatment retention, particularly in individuals with chronic fentanyl exposure Baxley, et al. 2023; Grande, et al. 2023; Weimer, et al. 2023; Bergen, et al. 2022. Alternatively, switching to long-acting injectable XR-BUP may address opioid use and cravings because this formulation delivers a higher steady-state plasma concentration of BUP than sublingual BUP/NLX Weimer, et al. 2023. In these and other complex situations, clinicians can contact expert consultants through the NYSDOH AI CEI Line (866-637-2342) and Providers Clinical Support System.

Long-term treatment: Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that long-term pharmacologic treatment is more effective at reducing nonprescription opioid use and retaining individuals in treatment than withdrawal management (previously known as “detox”) Fiellin, et al. 2014; Sigmon, et al. 2013; Weiss, et al. 2011; Gruber, et al. 2008; Woody, et al. 2008. In addition, withdrawal management without concurrent use of pharmacologic long-term therapy is associated with an increased risk of return to opioid use, overdose, and death Dowell, et al. 2022; SAMHSA(b) 2021; Bruneau, et al. 2018. A decreased tolerance to opioids developed during withdrawal management increases the risk of opioid overdose Kampman and Jarvis 2015. Despite clear evidence supporting the benefits of long-term pharmacologic treatment, further research to guide the specific duration is needed Dhanda and Salsitz 2021.

Individualized follow-up: After initiating treatment for OUD, follow-up patient contact and scheduling is based on the medication patients are taking and their individual needs. For patients taking BUP/NLX or XR naltrexone in an outpatient primary care setting, following up within 2 weeks of treatment initiation allows the clinician to tailor the treatment plan (e.g., change in medication dosage, addition of support services) to a patient’s needs and provide encouragement. As patients stabilize on BUP/NLX treatment, monthly or at least quarterly follow-up allows for ongoing evaluation to ensure that their goals are being met. For patients taking XR naltrexone, scheduled injections every 28 days are an opportunity to review the treatment plan and address any concerns. For methadone treatment, follow-up frequency is determined by clinical assessment of overdose risk and state and federal regulations governing OTPs.

During long-term treatment, ongoing follow-up is essential for support, encouragement, and modification of the treatment plan as needed. As with the treatment goals for other chronic illnesses, OUD treatment goals are individualized and likely to change over time, and continued engagement in nonjudgmental, health-enabling support can aid in the progression toward healthy goals. Clinicians and patients should discuss, agree on, and revisit OUD treatment goals explicitly and regularly. In general, if patients are not able to meet their goals, increased dosing of medication, more frequent visits, behavioral interventions, and/or mental health assessment and treatment may be warranted.

| Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; CYP450, cytochrome P450; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; OTP, opioid treatment program; OUD, opioid use disorder; XR, extended-release. | ||

| Table 1: Considerations When Choosing Buprenorphine or Methadone (Preferred Agents for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment) | ||

| Consideration | Buprenorphine | Methadone |

| Effectiveness | Treatment of OUD with BUP or methadone is associated with reducing other opioid use, promoting treatment retention, and reducing all-cause and overdose-related mortality. | |

| Patient preferences | May be preferable for patients who are new to pharmacologic OUD treatment, have had previous success with BUP, do not like or want to take methadone, or who have requested this medication. | May be preferable for patients who have had previous success with methadone, do not like or want to take BUP, or who have requested this medication. |

| Setting | Available through various treatment settings, including office-based prescription or specialty OTPs. |

|

| Initiation |

|

Opioid withdrawal is not required for initiation. |

| Titration |

|

Dose can be increased gradually to suppress opioid cravings and prevent withdrawal, with no maximum dose. |

| Adverse effects and safety |

|

|

| Medication interaction | Few clinically significant interactions with medications other than full opioid agonists. | Clinically significant interactions with medications that are metabolized by CYP450 enzymes can occur, leading to increased or decreased effects of methadone. |

| Counseling requirements | Not required unless legally mandated, but clinicians can refer for behavioral therapy and support services. |

|

| Treatment switch | Switching to XR-BUP or methadone is possible if needed to control opioid cravings and withdrawal despite maximized sublingual BUP dosing. |

|

Buprenorphine/Naloxone

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

BUP/NLX: Preferred Treatment

BUP/NLX Initiation

BUP/NLX Dosing

|

Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NLX, naloxone; OUD, opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder. Note:

|

Efficacy

Although BUP was developed initially as an analgesic, it was identified several decades ago as an alternative to methadone for OUD treatment Institute of Medicine 1995; Mello and Mendelson 1980; Jasinski, et al. 1978. BUP is a partial opioid agonist with a higher affinity for the mu-opioid receptor than heroin, methadone, and other opioids. It can displace full opioid agonists from mu-opioid receptors and replace them with partial activation. The opioid effect (or “ceiling effect”) of BUP is less intense than the effect produced by methadone or heroin. The high affinity of BUP for the mu-opioid receptor also has protective effects against opioid overdose. If a patient taking BUP/NLX takes a full opioid agonist, BUP will block the other opioid from activating mu-opioid receptors and prevent more intensive opioid effects, such as respiratory depression.

Extensive clinical trials and systematic reviews have demonstrated that, compared with placebo, BUP significantly reduces use of nonprescription opioids and improves retention in treatment Mattick, et al. 2014; Amato, et al. 2005; Ling and Wesson 2003; Mattick, et al. 2003. BUP treatment has also been associated with decreased risks of both all-cause and opioid overdose mortality Ma, et al. 2019; Larochelle, et al. 2018; Sordo, et al. 2017; Schuckit 2016. A systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies found that BUP treatment is associated with a lower rate of long-term treatment retention than methadone treatment Degenhardt, et al. 2023. Nonetheless, the relative differences in long-term treatment retention between BUP and methadone should be considered in the context of patient preferences and treatment access, with BUP being more widely available.

Formulations

Sublingual BUP/NLX: BUP is most commonly available as coformulated BUP/NLX in sublingual films or sublingual tablets, which contain 2 mg to 8 mg of BUP per film or tablet Mattick, et al. 2014; Ling and Wesson 2003. Sublingual BUP/NLX is typically taken as 1 dose or split into 2 to 3 doses daily, depending on the patient’s need for co-occurring pain management. Sublingual BUP/NLX is generally prescribed through community pharmacies for patients to self-administer.

Sublingual BUP: BUP is also available as monoformulated sublingual tablets. However, the BUP/NLX coformulation is recommended over the BUP monoformulation because it is less likely to be misused. When BUP/NLX is taken sublingually, only a negligible amount of NLX, if any, is bioavailable and clinically active. However, when BUP/NLX is injected, NLX is fully bioavailable and will delay the euphoric effects of BUP in individuals who do not already have physical dependence on opioids. Thus, the BUP/NLX coformulation serves as a deterrent to medication misuse. However, most diverted or misused BUP is used for OUD self-treatment and not for euphoria Carroll, et al. 2018. BUP/NLX coformulation is preferred over BUP monoformulation except in patients with hypersensitivity or allergies to NLX, which are extremely rare in clinical experience.

Injectable XR-BUP: Long-acting BUP (XR-BUP) is available as a weekly or monthly subcutaneous depot injection Lofwall, et al. 2018. Weekly injectable XR-BUP can be used to initiate BUP treatment in patients who are not already taking BUP; injections should be initiated immediately after a test dose of sublingual BUP to demonstrate tolerance without precipitated withdrawal. Monthly injectable XR-BUP is typically used with patients who have initiated treatment with a sublingual BUP dosage of 8 mg or higher for a minimum of 7 days, although varying initiation approaches can be used under specialist guidance.

XR-BUP must be obtained through pharmacies that are certified by the XR-BUP manufacturer’s restricted distribution program (see Sublocade REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] and Brixadi REMS). The medication is delivered to the prescriber’s practice by the REMS-certified pharmacy in anticipation of a patient’s injection appointment. Clinical programs or healthcare settings that wish to stock XR-BUP onsite must be certified in the XR-BUP manufacturer’s REMS. Brixadi (BUP) was approved by the FDA in May 2023 for OUD treatment as weekly or monthly injections and became available in fall 2023.

XR-BUP may be preferred to sublingual BUP/NLX for some patients with OUD, although evidence is just beginning to accrue. XR-BUP can achieve more stable and higher plasma levels than sublingual BUP Radosh, et al. 2022, which may be beneficial for patients with high opioid tolerance or with ongoing opioid withdrawal symptoms or cravings while taking the maximum daily dosage of sublingual BUP. XR-BUP may also improve treatment outcomes for patients who have difficulty adhering to daily dosing. In a randomized clinical trial, patients who initiated XR-BUP before release from jail had higher treatment retention than those receiving BUP/NLX Lee, et al. 2021. An observational study found high treatment retention rates among patients who received XR-BUP, even when most did not have stable housing Peckham, et al. 2021. In another recent randomized trial from Australia, XR-BUP was associated with higher patient satisfaction scores than sublingual BUP/NLX, although this study involved at least weekly visits and observed dosing for BUP/NLX Compton and Volkow 2021.

Insurance coverage: In New York State, as of March 2022, all formulations of BUP prescribed to treat OUD are covered under Medicaid fee-for-service and managed plans (see NYRx Medication Assisted Treatment [MAT] Formulary).

Opioid Withdrawal

The length of time after a full opioid agonist is stopped and withdrawal starts depends on the opioid’s pharmacologic properties. Known half-lives of full opioid agonists indicate that it may take at least 12 to 24 hours after the last dose of a short-acting opioid and at least 48 to 72 hours after the last dose of a long-acting opioid for a patient to experience opioid withdrawal symptoms. Although these time frames help set clinical expectations, individual experiences of opioid withdrawal may vary, and clinical management should be individualized.

Opioid withdrawal symptoms include increased heart rate, increased sweating, dilated pupils, restlessness, bone or muscle aches, muscle twitches or tremors, runny nose or tearing, gastrointestinal upset (nausea, vomiting, cramps, diarrhea), anxiety, irritability, goosebumps on skin, hot flushes or chills, and yawning. Clinical tools available to measure the severity of opioid withdrawal include the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale and the Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale Wesson and Ling 2003; Handelsman, et al. 1987. Clinicians can offer adjunctive medications, including clonidine, loperamide, and trazodone, to alleviate specific opioid withdrawal symptoms (see Table 2, below).

A patient’s recent opioid use history and review of the NYSDOH Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) Registry will help clinicians and patients anticipate withdrawal symptoms. Methadone and BUP dispensed from opioid treatment programs (OTPs) will not be included in the PMP.

Precipitated opioid withdrawal: BUP can displace full opioid agonists from mu-opioid receptors and replace them with partial activation. Before starting a patient on BUP/NLX, assess for and inform the patient about the potential for precipitated opioid withdrawal, the symptoms they may experience, and how those symptoms will be managed Cunningham, et al. 2011; Sohler, et al. 2010; Lee, et al. 2009:

- Educate all patients about expected withdrawal symptoms and distinguishing precipitated withdrawal as a sudden worsening of symptoms immediately after BUP/NLX initiation.

- Identify individuals with chronic fentanyl exposure; their risk of precipitated withdrawal may be greater than the risk for patients without chronic fentanyl exposure (see discussion of opioid withdrawal considerations in the context of chronic fentanyl exposure, below).

- Ensure that patients understand the potential severity of precipitated withdrawal symptoms and when to seek medical consultation. Provide patients with a clear plan of response to precipitated withdrawal, including how to contact a clinician.

- If precipitated withdrawal occurs:

- If the patient wants to continue BUP/NLX initiation, advise them to take additional higher doses (e.g., 8 mg/2 mg to 16 mg/4 mg per dose) and provide adjunctive medications for symptom management.

- If the patient decides to stop BUP/NLX initiation, engage the patient in shared decision-making regarding alternative treatment options and initiation strategies.

Opioid withdrawal considerations in the context of chronic fentanyl exposure: The onset and duration of opioid withdrawal may be variable and prolonged in individuals with chronic fentanyl exposure Huhn, et al. 2020. Pharmacologically, the risk of precipitated withdrawal during BUP initiation is higher with fentanyl than with heroin because of fentanyl’s high opioid receptor affinity, lipid solubility, and intrinsic agonist activity Greenwald, et al. 2022. People who regularly use heroin and fentanyl report increasing experiences of precipitated withdrawal and difficulty with standard BUP/NLX initiation, particularly when BUP is initiated within 24 hours of fentanyl use Sue, et al. 2022; Varshneya, et al. 2022; Silverstein, et al. 2019. In contrast, a recent prospective cohort study of patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) for opioid withdrawal reported a very low incidence of precipitated withdrawal after receiving BUP initiation doses of ≥8 mg, despite high rates of heroin and fentanyl use D'Onofrio, et al. 2023.

Although precipitated withdrawal is a serious concern, BUP can be initiated successfully with effective patient education and support. Continue to offer BUP, discuss patient concerns regarding BUP initiation, and consider an alternative BUP initiation strategy for patients who cannot tolerate opioid withdrawal or who have experienced precipitated withdrawal with standard initiation methods. Alternative strategies include:

- Low-dose BUP with opioid continuation (LDB-OC; previously known as microdosing or micro-induction) with an initial BUP dose of <2 mg and gradual up-titration while continuing full opioid agonist for a limited period; initiation does not require onset of opioid withdrawal (see guideline section Initiating Treatment, below) Cohen, et al. 2022.

- High-dose initiation with an initial BUP dose of > 8 mg and rapid up-titration within 1 day; initiation requires onset of opioid withdrawal D'Onofrio, et al. 2023; Snyder, et al. 2023; Herring, et al. 2019.

Current evidence and expert opinion favor the LDB-OC approach to BUP initiation in the outpatient setting, where patients are often evaluated when they are not in opioid withdrawal or are in mild withdrawal. Published experience with high-dose initiation has been with patients with moderate to severe opioid withdrawal evaluated in the ED D'Onofrio, et al. 2023; Snyder, et al. 2023; Herring, et al. 2019, and further research is needed to guide its use in an ambulatory setting.

| Abbreviations: FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. | ||

| Table 2: Adjunctive Medications to Relieve Acute Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms Reprinted with permission from Torres-Lockhart, et al. 2022 |

||

| Withdrawal Symptom | Medication/Class | Preferred Route/Dosage/Considerations |

| Autonomic hyperactivity, including muscle twitching, hot flushes or chills, restlessness | Clonidine (α-2 agonist) |

|

| Lofexidine (α-2 agonist) |

|

|

| Diarrhea | Loperamide (peripheral μ opioid agonist) |

|

| Insomnia | Trazodone (sedating anti-depressant) | Oral, 25 to 100 mg once daily at night |

| Doxepin (sedating anti-depressant) | Oral, 10 to 50 mg once daily at night | |

| Muscle aches, joint pain, headache | Ibuprofen (NSAID) |

|

| Acetaminophen (aniline analgesic) |

|

|

| Anxiety, restlessness | Diphenhydramine (antihistamine) |

|

| Hydroxyzine (antihistamine) |

|

|

Initiating Treatment

Setting: Home-based (unobserved) and office-based (observed) initiation of BUP/NLX treatment are safe and effective Cunningham, et al. 2011; Gunderson, et al. 2010; Sohler, et al. 2010; Lee, et al. 2009. The choice of setting is based on the patient’s comfort, preferences, and previous experience, as well as a clinician’s experience and support. The primary concern during initiation is precipitating opioid withdrawal, which can be deeply uncomfortable but can be ameliorated outside of an observed clinical setting (see guideline section Opioid Withdrawal, above). Individuals with OUD who are not in treatment may experience withdrawal symptoms regularly between doses of opioids over many years; patients’ familiarity with opioid withdrawal may be leveraged to help counsel and support them through home-based initiation. A patient’s preferences in managing their medications, including dividing BUP/NLX tablets or films into smaller doses, and access to telehealth for frequent check-ins can facilitate successful home-based initiation. Alternatively, observed initiation may be preferable for patients who do not have a safe space to prepare and store medications or manage potential withdrawal symptoms.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Standard initiation: The goals of treatment initiation are to control the patient’s opioid cravings, reduce withdrawal symptoms, and reduce nonprescription opioid use. With the standard approach to BUP/NLX initiation, the patient should experience mild to moderate withdrawal before the first dose is administered (see Table 3, below). The initial dose of BUP/NLX is typically 2 mg/0.5 mg to 4 mg/1 mg and is titrated every 1 to 2 hours in increments of 2 mg/0.5 mg to 4 mg/1 mg until the patient’s withdrawal symptoms improve. Advise patients to allow time (e.g., a few hours) for opioid withdrawal symptoms to improve after BUP/NLX initiation. The total dose of BUP/NLX taken on day 1 should be administered on day 2, with incremental dose increases if the patient continues to experience opioid withdrawal symptoms or cravings. The BUP/NLX dose typically stabilizes between days 2 to 7 during the standard initiation process, and the maximum dose of BUP/NLX is typically 24 mg/6 mg per day. For patient education on initiation, see the Addiction Training Institute: A Guide for Patients Beginning Buprenorphine Treatment.

Treatment may be initiated with higher doses of BUP/NLX (e.g., 4 mg/1 mg to 8 mg/2 mg) if a patient has prior experience with BUP/NLX, with dose titration up to BUP/NLX 24 mg/6 mg on the first day. Patients who are transitioning from long-acting opioids, such as methadone, to BUP/NLX may be at higher risk for complications during the standard initiation process Whitley, et al. 2010. Consulting with an experienced clinician may help determine the optimal initiation approach.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Low-dose BUP with opioid continuation (LDB-OC): This approach, which does not require waiting for onset of opioid withdrawal, may be appropriate for patients who are unable to tolerate waiting for onset of opioid withdrawal, have experienced precipitated withdrawal with standard initiation methods, are receiving full opioid agonist treatment for acute or chronic pain, or are receiving methadone treatment for OUD. Treatment may be initiated with a very low dose of BUP (e.g., 0.2 mg to 0.5 mg), followed by small incremental dose increases over 4 to 10 days. Patients can continue to take other full opioid agonists, including nonprescribed opioids until a therapeutic level of BUP is reached (typically >8 mg). Case reports on use in nonpregnant adults indicate that low-dose initiation is well tolerated and may reduce severity of withdrawal symptoms during BUP/NLX initiation Cohen, et al. 2022; Adams, et al. 2021; Ahmed, et al. 2021; Hämmig, et al. 2016.

Although high-quality evidence comparing the effectiveness of standard versus low-dose initiation strategies is not yet available to guide clinical care, different methods for LDB-OC have been described, with starting doses varying by availability of formulations and treatment settings. Table 4, below, provides an example of an outpatient protocol based on clinical review articles and the author’s experience at Montefiore Medical Center Cohen, et al. 2022; Peterkin, et al. 2022. Protocols can be individualized and can be shorter or longer in duration based on patients’ comfort and clinicians’ experience. Clinicians may wish to seek expert consultation in individualizing a treatment plan.

There are no strong data available to help patients use nonprescribed opioids safely during the BUP/NLX initiation process. A discussion of treatment should address the risks of ongoing use and strategies to maximize safety, including safer use practices and overdose prevention (see NYSDOH AI guideline Substance Use Harm Reduction in Medical Care).

For patients taking methadone and planning to switch to BUP, safely continuing methadone treatment during low-dose BUP/NLX initiation can be done via coordination of care with the OTP. Some OTPs can oversee the low-dose initiation process before transferring BUP treatment to primary care settings.

Clear instructions to guide a patient through low-dose BUP/NLX initiation should include: 1) when and how to split films or tablets; 2) how to manage daily dosing changes; 3) how much and how long to continue use of full opioid agonists; and 4) when and how to follow-up on concerns during the initiation process. Low-dose initiation requires splitting the BUP/NLX 2 mg/0.5 mg films or tablets. A quarter of a film or tablet is a 0.5 mg BUP dose; half of a film or tablet is a 1 mg BUP dose. When possible, arranging for a pill box during an office visit or coordinating with a pharmacy to blister pack BUP/NLX can be very beneficial.

| KEY POINT |

|

Maximum daily BUP/NLX dose: Although the maximum daily FDA-approved dose of sublingual BUP/NLX is 24 mg/6 mg, a higher dose of up to 32 mg/8 mg daily may be beneficial for some patients, including those with a high degree of opioid dependence who continue to experience withdrawal symptoms or cravings Baxley, et al. 2023; Grande, et al. 2023; Weimer, et al. 2023; Bergen, et al. 2022.

Before increasing the BUP/NLX dose beyond 24 mg/6 mg, clinicians should ensure that the patient is taking the medication as scheduled and is following the instruction to allow the pill to dissolve fully under the tongue rather than swallowing. Clinicians can also counsel patients to split the BUP/NLX for dosing 2 or 3 times per day. Dose increases above the FDA-approved maximum require close monitoring for treatment effectiveness and safety; documentation explaining the clinical rationale for such dose increases is advised given the potential need for prior insurance authorization. In New York, as of January 18, 2024, the state Medicaid program covers up to 32 mg BUP daily for OUD treatment without prior authorization.

As indicated, clinicians should also offer medication and psychosocial treatment to manage specific symptoms that may persist after acute opioid withdrawal (also referred to as protracted withdrawal or post-acute withdrawal syndrome), including anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances (see SAMHSA: Substance Abuse Treatment Advisory: Protracted Withdrawal) SAMHSA 2010. Other strategies for managing continued opioid withdrawal symptoms or cravings include the use of injectable XR-BUP or referral for methadone treatment, if available. Consulting with or referring the patient for consultation with an experienced substance use clinician may be needed to optimize the next steps of OUD treatment.

Adverse effects: Adverse effects associated with BUP/NLX are oral hypoesthesia (sensitivity), glossodynia (burning sensation in the mouth), oral mucosal erythema, headache, nausea, vomiting, hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), constipation, signs and symptoms of withdrawal, insomnia, pain, and peripheral edema FDA 2010. The bitter or bad taste of BUP/NLX is a frequent patient complaint in clinical practice. Dental problems have also been reported in patients after starting transmucosal BUP/NLX, although most cases involved patients with prior dental problems AMERSA 2022; FDA(a) 2022. Patients can be counseled on the potential for dental problems and the importance of taking care of their oral health after the BUP/NLX is fully dissolved, including spitting out residual saliva and rinsing their teeth and gums with water before swallowing. See prescribing information for full details.

| Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; DEA, Drug Enforcement Administration; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; LDB-OC, low-dose buprenorphine with opioid continuation; NLX, naloxone; OUD, opioid use disorder; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; XR, extended-release.

Notes:

|

||

| Table 3: Buprenorphine/Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in Nonpregnant Adults [a,b,c] | ||

| Formulations and Mechanism of Action | Dosing (individualized as indicated) | Considerations for Use |

| BUP/NLX sublingual film and tablet (multiple brands; see Medscape: Buprenorphine/Naloxone for more information)

Mechanism: Partial opioid agonist |

|

|

| BUP monotherapy sublingual tablets (multiple brands) | See BUP/NLX dosing, above. | See BUP/NLX considerations for use, above. |

| XR-BUP subcutaneous depot injections (multiple brands)

Mechanism: Partial opioid agonist |

Sublocade (monthly)

Brixadi (weekly or monthly)

|

Sublocade

Brixadi

|

| Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; NLX, naloxone.

Notes:

|

|||

| Table 4: Example Protocol for Outpatient Low-Dose Buprenorphine With Opioid Continuation [a,b] | |||

| Day | Dosing of BUP [c] | Total Daily Dose of BUP | Full Opioid Agonist Use/Administration |

| 1 | 0.5 mg once daily | 0.5 mg | Continue |

| 2 | 0.5 mg twice daily | 1 mg | Continue |

| 3 | 1 mg twice daily | 2 mg | Continue |

| 4 | 2 mg twice daily | 4 mg | Continue |

| 5 | 3 mg twice daily | 6 mg | Continue |

| 6 | 4 mg twice daily | 8 mg | Continue |

| 7 | 8 mg AM and 4 mg PM | 12 mg | STOP |

Approach to Tapering

There is no ideal duration for BUP/NLX treatment for OUD; long-term pharmacologic treatment is recommended over withdrawal management (previously known as “detox”); see guideline section Treatment Considerations > Treatment Options. Studies published to date have not identified clear modifiable factors that predict optimal outcomes with BUP treatment. Based on committee expert experience, patients treated with BUP long-term in the primary care setting can successfully manage OUD for a decade or more without resuming use of nonprescription opioids.

If a patient has a clear desire to taper and stop BUP/NLX treatment, the clinician should ascertain the patient’s reasons for doing so. Some patients may associate long-term OUD treatment with the stigma of taking an opioid agonist Bozinoff, et al. 2018. If stigma is a predominant factor in a patient’s desire to stop BUP/NLX treatment, education regarding the chronic nature of OUD may help the patient accept the need for long-term medical management.

If a patient decides to discontinue BUP/NLX treatment, clinicians should provide harm reduction counseling and NLX to reduce the risks of recurrence of use and overdose. Counsel patients that with an interruption or decrease in use, their opioid tolerance has decreased, which increases the risk of overdose, and emphasize that they can restart pharmacologic treatment at any time.

Offer a slow taper over several months, and provide NLX at each encounter. There are limited data to guide the speed and duration of a BUP/NLX taper. In a retrospective cohort study, BUP/NLX tapering undertaken after at least 1 year of BUP treatment and a slow rate of taper (mean rate of ≤2 mg dose decrease per month over the taper period) were associated with reduced risk of opioid overdose Bozinoff, et al. 2022. A mean taper rate of ≤2 mg per month over the taper period was also associated with a reduced risk of return to opioid use Bozinoff, et al. 2022. In general, a reasonable approach is to reduce the daily dose of BUP/NLX by 10% to 20% per month. Providing a slow taper is likely to lead to less severe opioid withdrawal symptoms and may be easier for patients to tolerate than a rapid taper.

Methadone

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Methadone: Preferred Treatment

|

Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; NLX, naloxone; OTP, opioid treatment program; OUD, opioid use disorder. |

Efficacy: Methadone is a full opioid agonist of the mu-opioid receptor. Full activation results in commonly known opioid effects, such as pain reduction, a sense of well-being or pleasure, and respiratory depression.

Clinical use of methadone for the treatment of OUD began in the 1960s Jaffe, et al. 1969; Dole and Nyswander 1965, and numerous studies have demonstrated methadone’s effectiveness in reducing nonprescription opioid use and improving retention in care compared with no treatment Kampman and Jarvis 2015; Mattick, et al. 2014; Mattick, et al. 2009. Methadone treatment has been associated with improvements in survival Sordo, et al. 2017; Soyka, et al. 2011, reduction in HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition and transmission Lucas, et al. 2010, improvement in quality of life Giacomuzzi, et al. 2003, improvement in birth-parent/fetal outcomes Minozzi, et al. 2008, and reduction in criminal activity Lind, et al. 2005.

Specialty OTPs: Methadone treatment for OUD is available only in specialty OTPs regulated by federal and state agencies. Regulations limit the number of patients that can be treated in each program and require observed dosing until patients are granted take-home doses based on established criteria. These restrictions have contributed to reduced access to methadone treatment for many individuals with OUD SAMHSA(a) 2019; SAMHSA(b) 2019. Effective for 1 year after the end of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, OTPs have increased flexibility to provide unsupervised take-home doses of methadone, potentially up to 28-day supplies, depending on the patient’s time in treatment and the OTP clinician’s assessment of therapeutic risks and benefits SAMHSA 2024. Flexibility in methadone take-home policies has not been made permanent, but studies show increased treatment engagement and patient satisfaction and no increases in overdose and diversion with take-home medication SAMHSA 2024; Hoffman, et al. 2022; Amram, et al. 2021.

Clinicians should be aware of OUD treatment options in the patients’ community and refer patients to an OTP when appropriate (see SAMHSA: Opioid Treatment Program Directory and NYS OASAS Treatment Availability Dashboard).

Because federal policies provide enhanced protection for individuals receiving substance use disorder (SUD) treatment (e.g., Code of Federal Regulations > Confidentiality of Substance Use Disorder Patient Records), clinicians should be aware that methadone dispensed from the OTP will not appear in the PMP; clinicians who are not affiliated with the OTP must also provide written patient consent to obtain information about treatment from the OTP. Communication between clinicians inside and outside of OTPs is important for many reasons, such as increased likelihood of identifying and managing potential drug-drug interactions and adverse effects (including central nervous system suppression) and overall health management.

Who to treat: Individuals who have a high tolerance for opioids or who have continued cravings while taking maximal doses of BUP/NLX may benefit from methadone, which is a full opioid agonist, to achieve optimal outcomes (see Table 1: Considerations When Choosing Buprenorphine or Methadone [Preferred Agents for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment]). Individuals with comorbidities, such as unstable serious mental illness or other untreated SUDs (e.g., alcohol use disorder or benzodiazepine use disorder), may benefit from an intensive treatment setting to optimize access to supportive services.

Adverse effects: Adverse effects associated with the use of methadone include constipation, lightheadedness, dizziness, sedation, nausea, vomiting, and sweating. Methadone use has been associated with life-threatening respiratory depression and QT prolongation FDA 2014. See prescribing information for full details.

Naltrexone

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Naltrexone: Alternative Treatment

|

Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; NLX, naloxone; OUD, opioid use disorder; XR, extended-release. |

Efficacy

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist (inhibitor) that binds to the mu-opioid receptor, causes no opioid effects, and fully blocks opioid agonists (heroin, methadone, and other opioids) from attaching to the mu-opioid receptor and causing opioid effects Bisaga, et al. 2018. Oral naltrexone is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for OUD treatment, although it is approved for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (see NYSDOH AI guideline Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder > Preferred Pharmacologic Treatment).

Clinicians can use oral naltrexone to confirm that patients have been abstinent from opioids, to test whether patients can tolerate naltrexone before administering an XR injection, or to supplement XR naltrexone if patients experience cravings or withdrawal symptoms during the 28 days between naltrexone injections.

The long-acting injectable naltrexone formulation (XR naltrexone) became available in 2010. Studies have demonstrated that XR naltrexone is more effective than placebo for OUD treatment Tiihonen, et al. 2012; Gastfriend 2011; Comer, et al. 2006, but only 2 randomized trials directly comparing BUP/NLX and XR naltrexone have been published to date Lee, et al. 2018; Tanum, et al. 2017. In 1 study conducted in the United States, participants randomized to receive BUP/NLX treatment had better outcomes, including higher treatment initiation rates and lower opioid return-to-use rates, than those randomized to receive XR naltrexone Lee, et al. 2018. In the other study, conducted in Norway, retention in treatment and the level of opioid use was similar in participants taking BUP/NLX and XR naltrexone Tanum, et al. 2017. Neither of these studies was conducted in a primary care setting; the U.S. study was conducted in community-based inpatient settings with outpatient follow-up, and the study in Norway was conducted in addiction clinics, where BUP/NLX was administered daily.

Furthermore, the risk of overdose among participants receiving XR naltrexone in the U.S. randomized controlled trial discussed above was nearly 4 times higher than the risk of overdose among those receiving BUP/NLX Ajazi, et al. 2022. Three large studies also found that XR naltrexone was not associated with decreased risk of overdose or all-cause mortality Wakeman, et al. 2020; Morgan, et al. 2019; Larochelle, et al. 2018. Additionally, a large observational study found that participants with OUD who were treated with XR naltrexone were twice as likely to discontinue treatment after 30 days than those receiving BUP/NLX Morgan, et al. 2018. In 2019, the FDA issued a warning letter regarding the increased risk of overdose following cessation of naltrexone treatment for OUD FDA 2019.

Who to Treat

Injectable XR naltrexone may be considered if BUP or methadone is not accessible or desired. Methadone and BUP are preferred over XR naltrexone because of the survival benefit associated with opioid agonist treatment among individuals with OUD Wakeman, et al. 2020; Morgan, et al. 2019; Larochelle, et al. 2018. In particular, BUP/NLX is currently preferred over XR naltrexone based on the results of clinical trials Lee, et al. 2018; Tanum, et al. 2017 (see discussion above), the practical challenges of initiating and maintaining XR naltrexone treatment, and the low number of patients who choose XR naltrexone over other options Brooklyn and Sigmon 2017.

Initiating treatment with XR naltrexone requires patients to be fully withdrawn from opioids, which is difficult for many patients, particularly in outpatient settings. In the U.S. randomized controlled trial described above, 28% of participants assigned to XR naltrexone did not complete the initiation phase versus only 6% assigned to BUP/NLX Lee, et al. 2018. The initiation process is likely part of the reason few patients choose to take XR naltrexone. In real-world practice, of 3,639 patients with OUD being treated in Vermont (where all treatment options are generally available), 2,565 were taking methadone, 1,055 were taking BUP, and 2 were taking XR naltrexone Brooklyn and Sigmon 2017.

Clinicians should emphasize the need for adherence to XR naltrexone for OUD treatment. Clinical trials evaluating XR naltrexone for OUD treatment have demonstrated that adherence is essential to achieving a reduction in nonprescription opioid use and improving retention in treatment Jarvis, et al. 2018; Lee, et al. 2018; Tanum, et al. 2017. The initial clinical studies with XR naltrexone were performed among highly motivated individuals who were at risk of losing their jobs because of OUD Saxon, et al. 2018. A registry study found that factors associated with longer-term adherence were employment at baseline, private health insurance, normal mental status/minimal mental illness, school attendance, and less prior drug use Saxon, et al. 2018.

Initiating Treatment

Before initiating XR naltrexone, inform patients of the following:

- There is a risk of prolonged opioid withdrawal if opioids are still in the patient’s system when XR naltrexone is administered.

- Unlike BUP and methadone, XR naltrexone will not relieve withdrawal symptoms.

- There may be an increased risk of overdose if opioids are used after stopping treatment with XR naltrexone or toward the end of the 28-day dosing interval. Although overdose can occur when opioids are used after stopping any medication for OUD treatment, the risk is particularly high after stopping XR naltrexone, relative to BUP or methadone, because of the substantial reduction in opioid tolerance with XR naltrexone.

Prescribing information indicates that individuals should be abstinent from opioids for approximately 7 to 14 days before initiating XR naltrexone FDA 2013: 7 days for patients using short-acting opioids and 14 days for patients using long-acting opioids (e.g., methadone, XR formulations). During this period of opioid abstinence, individuals with OUD will experience moderate to severe withdrawal symptoms.

To confirm that an adequate length of time has passed since last opioid use (“washout period”), clinicians should perform an NLX challenge by administering intranasal NLX as available and observing the reaction (see Table 5, below). In individuals with recent opioid use, this may precipitate opioid withdrawal. If intranasal NLX is not available, consider a challenge with oral naltrexone, starting with a low dose (e.g., quarter of a 50 mg tablet or as available). If a patient is already taking oral naltrexone, an NLX challenge is not necessary.

In patients confirmed to have an adequate washout period but who have not previously tried naltrexone, a brief regimen of oral naltrexone can be used to confirm medication tolerance before administering the long-acting injectable formulation (see Table 5, below). Oral naltrexone is not approved by the FDA for OUD treatment, but it is used to initiate the treatment cycle for XR naltrexone. Alternatively, to shorten the initiation period for XR naltrexone, very low doses of naltrexone can be initiated in combination with a BUP taper without requiring a full opioid washout period Bisaga, et al. 2018. Oral naltrexone doses can be gradually titrated up to full blocking doses within 7 days to demonstrate naltrexone tolerance.

Once it is confirmed that a patient can tolerate naltrexone, an injection of XR naltrexone (380 mg intragluteal) may be administered every 28 days. It can be administered every 21 days if patients have breakthrough cravings. If injectable XR naltrexone is not immediately available, or if patients have breakthrough cravings during the cycle, oral naltrexone may also be taken.

Adverse effects: Adverse effects associated with XR naltrexone use include protracted withdrawal, nausea, vomiting, injection site reactions (including induration, pruritus, nodules, and swelling), muscle cramps, dizziness or syncope, somnolence or sedation, anorexia, decreased appetite, or other appetite disorders FDA(b) 2022. See prescribing information for full details.

| Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; NLX, naloxone; OUD, opioid use disorder; XR, extended-release.

Notes:

|

||

| Table 5: Extended-Release Naltrexone for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in Nonpregnant Adults [a,b] | ||

| Formulation and Mechanism of Action | Dosing | Considerations for Use |

| XR naltrexone (Vivitrol)

Mechanism: Opioid antagonist |

Initial and long-term treatment (intragluteal injections): 380 mg every 28 days

|

|

Pain Management for Patients with OUD

Individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) often have co-occurring pain, including acute and chronic pain. In general, patients who are taking buprenorphine or methadone for OUD treatment should continue to take their long-term treatment dose while optimizing nonopioid medications and nonpharmacologic treatments. Temporarily increasing the buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone dose or splitting the dosing frequency may be effective for managing acute pain; the addition of a short-acting full-agonist opioid can be considered for management of moderate to severe acute pain ASAM 2020. When adding a full-agonist opioid analgesic, patients will likely need a higher dose than opioid-naive patients to achieve adequate analgesia ASAM 2020.

Detailed recommendations for pain management for patients with OUD are beyond the scope of this guideline. Clinicians are advised to consult the American Society of Addiction Medicine National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update > Special Populations: Individuals With Pain.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: TREATMENT OF OPIOID USE DISORDER |

Overdose Prevention

Who to Treat

Treatment Options

BUP/NLX: Preferred Treatment

BUP/NLX Initiation

BUP/NLX Dosing

Methadone: Preferred Treatment

Naltrexone: Alternative Treatment

|

Abbreviations: BUP, buprenorphine; ED, emergency department; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NLX, naloxone; OTP, opioid treatment program; OUD, opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder; XR, extended-release. Notes:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

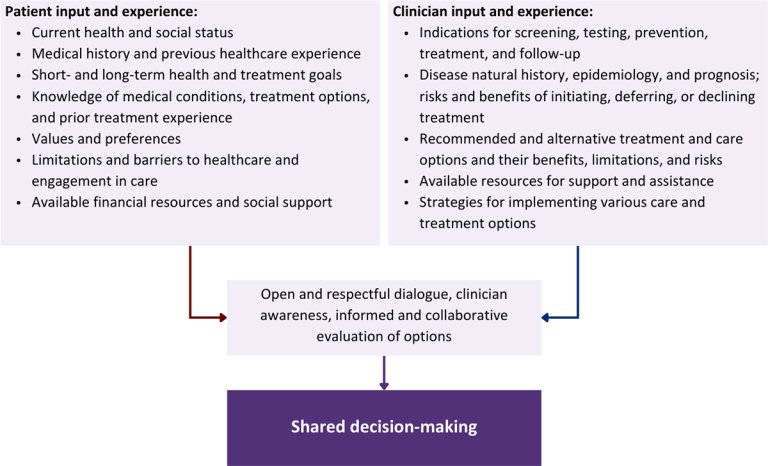

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf